When the Commerce Guild of Sashim can't find a volunteer to play the role of the spirit to be venerated at the annual festival, a wandering bard finds a likely candidate and offers to escort him through the city and the ceremony...only perhaps the handsome stranger railroaded into the part isn't quite what he seems.

10,029 words, please view PDF for full text, proper formatting, and illustrations (also visible here: https://www.furaffinity.net/view/53471833 )

---

“It just won’t be the same this year,” opined a lynx, tugging at a tufted ear while waiting for his turn at the market stall.

“I’d volunteer,” offered an apologetic-looking zebra, “but the paint they used last time made me break out in a rash.”

A rhino in line behind them added, “I can’t believe there isn’t a white horse in all of Sashim.” He paused, stroking a contemplative horn, “At least, none as will volunteer, if only for the weather.” Unspoken was the commonly held superstition that a well-performed ceremony would settle the winds and waves. And the always looming specter of possibility: that if conditions didn’t improve, the traders and fishers on whom the city depended would find friendlier harbors, leaving Sashim a ghost to be swallowed up by its own rebellious bay.

“I heard that the real Gwyntus hasn’t been seen in a generation,” said a wistful old woman, “Or was it a century? I can’t remember. That’s why the weather has been so fickle, and why it’s so important to have this ceremony: to remind the winds of their master.”

“Oh yes, grandmother,” her hearers agreed respectfully, though few actually believed that such an enjoyable event (irritating makeup aside) could actually be the cause of atmospheric change.

¶ß

The conversations all throughout the “city on the sea” were going in much the same tack. The Sashim Commerce Guild—a guild of guilds, as it were, whose membership was comprised of representatives elected from the Guild of Merchants, the Scribblers’ Guild, the Association of Costermongers, and similar professional organizations—was wringing its collective hands with worry. The sole volunteer for the day’s centerpiece role had come down with Green Gore, and nobody blamed the white mare for bowing out. Bedridden and vomiting from contaminated water (likely from a stagnant cistern, suggested a wag from the Laborers’ Guild; but everyone knew that he had aspirations to be Commissioner of Works, and therefore took every opportunity to pin fault on the current officer), there was no way she could have donned the requisite costume to prance about the bridges and hexagonal basalt pillars of Sashim, let alone perform the other expected duties.

So now, like a harvest festival with no harvest, the Gwyntus Vindur celebration was set to begin without Gwyntus Vindur himself. Across the city, horses, donkeys, and zebras repeated similar excuses to friends and strangers alike; after all, the role was hardly mandatory, and the celebration would go on with or without the deity it honored.

¶ß

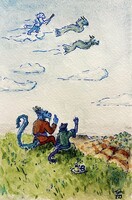

In one of the city’s many six-sided squares—with open water on one side, a cistern in the center, and backed by the colonnaded façade of a Temple to Concord—and beneath the spidery shade of an ornamental oak bereft of leaves, a bard had set up shop. The ornate painting of his handcart-cum-podium proclaimed him to be “Kibou the Captivating,” who had performed in Gulporte and Bayard and Midsune. The lung dragon began with the usual assortment of seasonal songs, their familiar words and tunes drawing in passersby: “My Love’s Cheeks are Redwinter Berries,” “How Cold the Lonely Hearth,” and the humorous local favorite “My Clock is Frozen, How About Yours?” His pearly scales and mint-green mane attracted attention nearly as much as his buttery voice, so when a suitably large crowd had encircled him, he stood, turning the slow movement of legs stiff from long sitting into a graceful unfolding of stocky limbs and long spine. A solid strum across the strings of his death’s-head lute caught the ear of any stragglers and alerted all to the fact that a story was about to begin.

Chill sunlight glinted warmly off the gold threads that hemmed his robe and obi, and gold were the bells strapped to his tail. Kibou rattled them with a whipcrack undulation of its length, shushing any chatterboxes and giving his words space to expand.

“I sing,” he began, (though the tale was prose and not poetry) “of wind and of rain, of soil and root and crop, of the end of some things and the beginning of others.” The lute reverberated as his fingers nimbly plucked a gentle scale.

“In the old days, before our world became what it is, balance was unknown—“ a minor chord, “—there was uncertainty—“ a sharper discordant tone pair “—and loss.” The lung’s tail, with its burden of bells, shook like a mourner’s sistrum. “In short, my tale is of the Invention of Weather.” So perked were the listeners’ ears that not one took notice of an extra figure in their midst, a tall white horse of statuesque musculature and bearing. He listened with curiosity, as though he’d never heard the famous legend before, an occasional breeze rippling his unadorned tunic.

A subtle shift to the twitching of Kibou’s tail altered the bells’ tintinnabulation to match the story’s proper beginning:

¶ß

The weak west wind hissing through the branches of the dying trees made a sound like a cloudburst, an illusory downpour. The taunting noise was alien to the children who heard it, and a fading memory to the older folks who looked up at the iron skies with forlorn hope. No matter how they wished or prayed, there simply…

…was…

…no…

rain.

The aquifers were running dry, and the wells they fed—the wells that farmer and herder and householder alike depended on—now gave forth little more than mud. Cisterns and rain barrels held only dust, dry air, and the nests and carapaces of countless generations of insects. Eret, that town we now all know as the greengrocer of our nation, was dying.

The town elders held council in the central warehouse: after hearing several proposals (sinking more wells, the purification of swamp water, sacrifices to various gods, or even the search for a spell to draw water from the air itself) the decision was made to hire a tanker cart to haul water from the rivers springing in the Karal Range to the south. But after so many fruitless years, the village’s meager remaining savings wouldn’t suffice for more than one trip of what was effectively a big tavern barrel on wheels. There would hardly be enough water for one farm, let alone the entire township.

Then a lone farmer stood from the back of the assembled men and women. He ran a hand through his dark black mane, as though trying to calm his nerves, his hide as dull and dusty as everyone else’s in the town’s vast and empty warehouse. The cavernous space fell silent as he cleared his throat. “It seems to me,” he said, measuring his words like bushels of grain, “that our only option is to seek help of a less…ordinary sort.”

“But we tried prayers,” the replies came from all sides, “and sacrifices, and ceremonies, and our parents hired that charlatan of a wizard who said he could magik water out of stones.”

“Aye. But we have not gone in person to present our pleas directly.” He held up his hands—rough from long and futile labors—to forestall any protests. “My farm is dead, my crops withered beyond rescue. Even if there were water enough in a tanker cart to saturate my fields, it would not come in time to save them. I will take what food I have left and go north.”

“To the Wind House?” exclaimed the familiar voices around him, marveling at the audacity of the suggestion. He might as well have suggested that he would seek out the ancient geniuses and genies of fallen Nordant, or travel across the seas to the Forbidden Jungle of Klodrai for a solution to their collective plight.

“Indeed. If I perish in the attempt, then it will be no different from my fate if I remain,” he said, standing resolute against the rising tide of argument. “And if I do succeed…” His open palms said more than his simple words could have, and quelled all further protest.

The elders agreed: the farmer would embark on his journey north, as others would go south to continue the original plan. One way or the other, the farms must have water; two seeds in the furrow were better than one. So the farmer gathered his meager provisions—including donations of journeycake and other way-food—wrapped puttees around his hocks, and left his village without another look back. If he failed—even if he succeeded—he was not likely to see his home again, but being a practical man he knew what had to be done, regardless of the outcome for himself.

He trudged along for league upon league, past dried-out forests and flooded deserts, villages abandoned to time, and various other signs of the disorder of the world. The sun seemed to bounce from one horizon to the next, sometimes westward, sometimes eastward, fast and slow, while the winds buffeted him before and behind, tugging at tail and mane, cloak and pack. “Stop this madness!” he cried, holding onto his clothes lest they be rent from his body by the impish winds, using his cedarwood staff as a prop against being overturned.

None answered his plea.

The horizon stretched before him now, flat and featureless, with flurries of dust or powdery ancient snow—he couldn’t tell which—kicked up by the same whirling gusts that threatened to spin him around until he had utterly lost his direction. There were no mountains, not even the husk of a dead tree to fix his eye on as a waypoint, and in those ancient days before compass and astrolabe he had only the crazy dance of sun and stars to indicate his goal. Stolidly he trudged on.

A vast wall rose up ahead of him, as though the ground had been carved away by a giant’s cakeslice. It seemed to stretch on forever, with neither break nor deviation for as far as he could see in either direction. There were no hand-holds, neither grooves nor crevices to fit his hooves into, no stair carved up nor ladder dangling down. He sank to his knees, shouting wordlessly with his despair: he had one, maybe two days of provisions remaining, and little enough strength to consume them, let alone decide on a direction of wall and then follow it in the baseless hope that it would at some point end.

“I’m sorry,” he wept, his voice hoarse with the cold, “I failed.” The foolish certainty of his success no longer bolstered him no longer shielded him from the hardships of his journey, the deprivations of so many long years without rain. What good was it to eat the remaining morsel of stale bread, drink the last swallow of murky water, to stay alive for a few days more, when there was no hope for salvation, neither for himself nor for his village. Perhaps the tanker cart would suffice to rescue them.

He fainted dead away.

¶ß

The lung ceased his tale, the bells on his tail preternaturally still as he looked about his audience. They all leaned forward where they stood or sat, ears open to catch his next word, eyes wide but unseeing, so absorbed were they in the picture Kibou had been painting in each of their minds.

He took a languid pull from his waterskin, the subtle infusion of sage, mint, and chamomile tingeing the taste and soothing his throat. Just as a fiddler might rosin her bow mid-performance, Kibou the Captivating had long ago learned the importance of tending to his own primary instrument. Filling his mouth with another swig, he let his fingers dance across his lute’s strings, calling up a mysterious theme as his tail shook off its stillness and added a cascade of sound, as though the listeners were enveloped by the leading edge of an approaching blizzard.

The horse alone stood unmoved, his brow furrowed and hand stroking his chin as though lost in thought, or trying to recall an elusive memory. Perhaps he’d heard the story differently in his village, Kibou surmised, shrugging off the one auditor who hadn’t thus far fallen under his spell. But there was the rest of the tale yet untold, and he’d never left an audience unsatisfied. They don’t call me “the Captivating” for nothing.

The strummed melody shifted again, weaving strains from different lullabies into a soothing tapestry of familiar sounds. He let the last trickle of cold herbal water caress his throat, then resumed the story. “The horse awoke in a magnificent hall, on a bed of cloud covered by sheets of mist. At his stirring, he heard ghostly footsteps dancing around him,” the tail rattled lightly, so that only the smallest of the bells tinkled.

¶ß

“Hello?” he cried weakly, then succumbed to a coughing fit; blackness crept along the corners of his vision and he fell back on the cumulus pillows, exhausted. A few moments of focusing on his breath, on the pulse throbbing through his ears, the weary stiffness of his legs, helped to calm him, ground him in reality…and help him ignore the growing ache in his chest.

“Hello? Is someone there?” he asked again in a gentler intonation, hearing wordless whispers in the corners of the cavernous room.

“They’re afraid of you,” intoned a mournful voice from the side of his bed.

The farmer looked down and saw a tiny figure, a lithe vixen swathed in fog who stood barely taller than his hock, the hair of her beautiful human face streaming down to mix with her diaphanous garment. “Who are you, little one?”

“I am the speaking wind, I hid in caves and forests and lured travelers to their doom by sounding like a familiar voice.”

The horse recoiled and tucked his legs up under his cloudy blanket. He had heard the stories of this particular yokai, who was just one of many spirits the mortals of his era had to fear. “You’ve kidnapped me!”

“No,” she said, tears spangling her ebony locks and a blush coloring the pale skin of her face. “I am myself a captive in this place. In penance for my victims, I now must serve as steward and majordomo. My masters bid me to bring you to them once you had awakened.”

“Then those other voices…?”

“Those are the Tame Winds. They stay within the palace here, skittish as pet mice, tending to chores. I am in charge of them—which is penance enough in itself—and must ensure they perform their duties. While they stand guard, the Brothers placed the Tame Winds here to protect them from the Wild Winds.”

Though his head was swimming with questions, the farmer slid from the bed and stood shakily on his hooves. The staff which had helped him to cross the leagues from Eret was propped up beside the bed, its familiar grain welcome under his fingers as he picked it up to aid his unsteady steps. Perhaps by speaking with these Brothers he might get a straight answer. A flickering hope raised its tentative flame in his breast: perhaps his mission…but no, he couldn’t allow himself to complete that thought, even in the secret depths of his heart, lest the breath of excitement snuff it out.

The irony was not lost on him as he followed the Speaking Wind through the echoing, whispering halls, then down a spiral stair and into a vast barn-like space. It was shaped like a triangle, with a vast archway set into the center of each wall. Three men, horses all, stood guard, each one filling the archway where he was stationed. Perhaps it was a trick of the light, but as the farmer looked around, he noticed a brightness shining through them where brightness ought not to be. It was as though they had a hole cut through them, one’s belly, another’s face, and the third’s forehead each showed the sky beyond.

His courage failed and he stopped on the final step, one hoof raised above the barn’s floor. The guards didn’t move, with only the rise and fall of their shoulders and the swell of their backs to show that they were alive. After a moment, the farmer relaxed slightly, and his leg shifted, lowering, until his hooftip brushed the packed dirt.

The horses spun around as swiftly as whirligigs, staring at the intruder, their faces impassive and inscrutable. The farmer quailed, falling back against the stairs, his tunic fluttering as the minuscule yokai rushed over his body. “My lords,” the fox with a human’s face said, bowing low as her tail swept the ground, “this is the visitor we found outside the walls. He has been restored to health and begs leave of an audience with yourselves.”

They looked from one to the other, as though uncertain how to proceed. Finally one of the trio stepped forward, and as though perspective had reversed its laws, as he drew nearer he lost his fearsome aspect; by the time he stood before his guest, they were of the same stature. “I feared you might never awake,” the sorrel horse said, though the farmer couldn’t see how: the horse had no muzzle, neither lips nor tongue, but only a circular hole beneath his eyes, punched straight back through to his mane. This didn’t seem to affect the horse, who continued: “When our half-tame winds—the ones brave enough to patrol the perimeter of our palace—found you, they thought you were an ice statue left by zealots or carved by the Wild Winds.”

The farmer laughed, “But since when has a black horse looked like ice?”

“Black? Are you certain?”

The farmer held out his arm as proof, pulling up the tunic’s sleeve for good measure, then stared at the hide thus revealed: it was as white as the driven snow, pearly as frost and soft as laundered linen. He ran a hand across it, roughing it up with his nails in the hope that black roots might be revealed, but even the skin beneath was white. He’d been bleached by the sun and the frost, drained of all hue. He fell back against the bulk of the stairs, dropping his staff and clutching at his chest. His journey had cost him so much already, and now even the color of his hide had been sacrificed, stolen away by the Northern Wastes.

But the faceless horse smiled—or seemed to, from the way his missing cheeks squished the corners of his eyes—and turned to the farmer, holding out a hand to lift him to his hooves once more. “What quest has brought you to our halls?”

“My name is Gwyntus of Eret, and I have come to beg assistance for my village. Your steward,” he nodded at the diminutive figure, “mentioned Tame Winds and Wild Winds, so I hope that my pleas may fall on the right ears. Do you three control the winds of the world?”

“Yes,” the horse said, though his reddish ears canted back as though the word didn’t quite do justice to reality.

“Then you can help me! My village—for we are farmers all—is dying; we have had no rain in many long years, not since I was a foal myself. Our aquifers and wells are dry, our reservoirs long since emptied, and all nearby rivers are nothing but stony grooves in the land. Have we caused you anger through some misdeed, some impious word? Have we omitted some act of supplication? Please, tell me how we have offended, that I might make it right.”

“Eret, you said?” He toyed with the lavender broom he carried in place of a guardsman’s sword. “No,” he finally conceded, “your drought cannot be of our manufacture, for we control the winds, not the waters.” Then the sorrel horse looked at his brothers, saw the nods and downcast eyes. He cleared his throat. “Unless…I wonder: in your village, are the winds fitful or strong? Do they come from one direction or many?”

“Fitful, and from all directions.I remember in my youth that each season would have its winds, steady and strong enough to fly the heaviest kite, but now they only stir up dustwhirls and throw grit in our eyes.”

The sorrel horse blustered through nonexistent lips. “Then I regret to tell you that your plight is indeed our doing—though no fault of yours, nor your village’s.” He added, placing a hand on his guest’s shoulder. The warmth and tenderness of his contrition made the farmer’s eyes well up with tears, tears that frosted into snowflakes as his eyelashes batted them away.

“If only,” the sorrel continued, “we could leave our posts, we might remedy this problem.”

“But why? Why can’t you?” the farmer asked, staring at the glittering ice stars his own eyes had created, a miniature snow drift in the whitened hairs of his palm.

¶ß

The lute strings, held against the instrument’s neck, produced brittle-sounding high notes: the sound of crystalline tears delicately shattering. Kibou looked around his audience, tense faces expressing the same desperation as the protagonist, the more emotionally-sympathetic among them with non-snowflake tears in their own eyes. And among them stood the horse, motionless, eyes unseeing, staring not at the lung minstrel but through him. An odd one, that, Kibou thought, but there was story yet to tell.

“We got…distracted with a dice game,” he said in the voice of the faceless sorrel horse, rattling his tail like the wooden cubes in a bamboo cup: taka-taka, taka-taka, skoosh as the imagined dice scattered across a table, then taka-taka again for the next hand. “We were tasked with guarding the Wild Winds here, and so engrossed were we in the diversion that we each thought one of the others was still standing guard.”

Some of the older heads in the audience shook ruefully, knowing first-hand, perhaps, the dangers of gaming, and certainly of immoderate distraction from one’s duties. One or two of the youngest faces stared horror struck: could a simple game of dice have thrown the world into such disorder? Kibou smiled to himself, proud that he could weave some morsels of instruction into his entertainment. The lute strings cascaded mournfully as the horse continued his explanation.

¶ß

“But of course there are only three of us, and three doors to guard, and three filled seats at the dice table. Because of our negligence, all the Wild Winds escaped out into the world, so now we stand here, guarding our empty barn in case they come back.”

“You are waiting, here,” the farmer repeated slowly, dumbstruck, “guarding an empty barn, in the hope that these Wild Winds will return to their captivity? On their own?”

“What else can we do?”

He looked around at the chagrinned and ashamed Brothers: the sorrel with the hole beneath his eyes and the lavender broom held limply in his fingers; the dun, whose hole was in his forehead, nervously waving a palm frond fan at himself; the hole-bellied chestnut leaning on a rake of oak wood and refusing to meet his eyes. “You could leave yourselves! Or you could ask for help,” he said, tempering his frustration with mercy. After all, how could these three have known the havoc their negligence would birth?

Moving as one, the three horses turned to him. “Will you help us?” they pleaded.

How could he say no? He had expended all his property and energy in reaching this point, and it was not enough to merely know the cause of his village’s suffering. Whatever the cost, he had paid and would pay it gladly so that he might complete his mission. So that his village might live.

At his assent, the Brothers summoned the Speaking Wind to prepare the farmer for his journey. She had been loitering by the spiral stair and had heard all.

First she removed his clothes, and then recited a magic spell while she traced a circle around his chest. Like a circle cut from cookie dough, the cylinder of flesh lifted out easily, hovering above her waiting palms. The farmer stared at this piece of himself—even as it began to crumble and dwindle like ash in the wind—then looked around at the brothers: had they each undergone this process too?

His torso—thickened by labors and hardened by long privation—was just as it had been, albeit white as foam, but between nipples and navel was a great circular nothing. The same as the three men standing around him, he now had a hole drilled through his body, and yet did not die. Nonexistent heart beating hard in his ears, he looked at the faceless horse, his own face a rictus of confusion.

“Welcome, brother. Welcome to the Wind House. You are a Vindur now, you are one of us,” the three said together.

“Sacrifices, brother,” said the sorrel, placing a tender hand on the farmer’s shoulder, “must be made. To have any power over the wild wind, we each had to give up something dear to us. My voice, his mind, his stomach…and your heart.” And he introduced the other horses. Lanwyn Vindur, the faceless sorrel horse with his lavender broom mastered the spring winds; dun Hafpanas Vindur, with the forehead hole and palm frond fan, was in charge of the summer winds; the empty-bellied chestnut horse with his oaken rake was Raugdref Vindur, and his winds were the gusts of autumn. He turned to the newest addition, the formerly coal-black former farmer who still clung to his staff of cedarwood. “And you, Gwyntus Vindur, shall be the keeper of the winter winds.”

The words, the names, the knowledge, each sent their separate chills along his spine.

The Brothers showed him how to talk to the winds, how to wrangle them, and herd them. At first the hole in his chest would ache with every new skill he learned, every time he exercised his new powers, as though to remind him of the price he’d paid. He also quickly learned to block that part of him when sparring, lest any errant breeze he sought to capture might use that opening to escape, the sharp air setting his teeth on edge. He was taught the types and names of the winds, and how to use his staff of cedar as an extension of his will and arm, finding the techniques and attacks best suited to his physique and ability. In short, they prepared him to fight the battles they could not.

One night, when Gwyntus was trying to sleep, the Speaking Wind stole up to his bedside. “Did you see how large was the circle of flesh I removed? That sacrifice is commensurate with the power bestowed, as befits the man in charge of the most powerful winds. With your new strength, you could overthrow the other three, punish them for their heedless laxity! You could take control and free me! You could be master of this world…with me at your side as your advisor and confidant.”

But she had misjudged her quarry, for no pretty words would distract him from his goal. “Begone, foul yokai, and trouble me not with your temptations! I crave neither power nor control, and I know that to free you would return you to your treacherous ways. Order alone is what I desire, the order of the seasons marching in their circle, each following the other as it was in the past, as I only dimly remember from my childhood. My goal is to restore that cycle, nothing more. Begone.”

The Speaking Wind wafted away through the halls, muttering echoed curses. She was powerless to disobey, for she had indeed made Gwyntus more powerful than his new brothers, the most powerful controller of winds. And while he was grateful to have been saved from a frozen death, while he would come to be glad of the strength he now wielded, the Speaking Wind had read too much of herself into him: he would not turn false, would not forsake his duties (neither new nor old) merely because the opportunity presented itself. There were more important things than the fleeting whims and temptations of a wily yokai.

She broke her bonds that night, before he could grow into his full potency. Leaving her echo to throw off any search, the Speaking Wind hid herself in the deepest caves, ever-roaming, never still. Caves where she still lurks to this day, luring the unwary with all the cold-burning ferocity of a lover spurned.

The next day, the Brothers presented Gwyntus with a pair of league boots: these would not only protect and support his legs better than his rough puttees had, but had the added benefit of being imbued with potent magic. They allowed their wearer to “tread the winds,” turning an easy stroll into a leap across the sky, spanning a league with every step. Recalling how long it took him to reach the Brothers’ northerly palace, Gwyntus was grateful that his return journey would be far swifter.

Tucking his trouser cuffs into the leathern tops, he reached for his tunic, but the arduous journey had taken its toll on the already threadbare material, and the Speaking Wind’s fingers had been none too gentle when she’d removed it. So Raugdref, the chestnut-hued Brother and keeper of the first chill winds of autumn, looked him over like a tailor taking measurements. He stepped back, put his hands in the hole piercing his belly, and withdrew a gust of air that became increasingly visible as he ran it through his hands. As a baker kneads bread, Raugdref Vindur massaged the gust in to a length of blue fabric, a sash to wind from Gwyntus’ shoulder to his opposite hip, and then knot around his waist. Barring the sash’s color and the trousers he wore, he now was dressed just like his new brothers.

Thusly arrayed, he strode across the world, arriving in a matter of minutes at the coast to the eastnorth of his village. His new powers and brief training gave him a knowledge of the winds, an awareness of their location and strength—far superior to what our weather sages can forecast today, even with the aid of airship observatories—and he knew instinctively that here was the culprit, the cause of all his village’s suffering. He saw with wintry eyes unclouded by mortal failings, the unseen rendered visible, masks and spells and glamours alike falling away.

A large creature hovered in the air, like a lion with a black mane and hands of stone and a lung’s tail whipping him back and forth across the sky. He roared in devious pleasure as he blew against a veritable herd of other wind spirits: wooly-headed fish, whose satyr horns were ineffective against the mischievous wind’s rocky fingers, and whose cold and water filled hearts held no courage. They bleated weakly as he held them at bay. The lion-headed wind saw Gwyntus approaching, and turned to face the horse. “Who are you and why do you dare—“ then he saw the hole in the horse’s chest behind the fluttering blue sash, and recognized the mark of the Brothers. “A Vindur? I do not recognize you!”

“I am new,” Gwyntus said calmly, holding up his staff. “Wild wind, Dil’gud of the West, I recognize you, and command you to leave off your mischief!”

They battled, but it was like a child struggling against a star brawler of Dagune’s Arena. For every ferocious stone-clawed swipe, Gwyntus merely had to step out of the way, his league boots carrying him effortlessly across the sky. Then he would step right back and knock Dil’gud with the butt of his staff: a tap on the head, a buffet to the shoulder, a prod of the tail. The stone claws were blunted, and the Wild Wind’s eyes crossed. After an hour of fighting, the leonine gust succumbed and begged mercy.

“Mercy you shall have. For your penance, you must return to the care of the other Vindurs, and bring with you every Wild Wind you meet on the way. I will know if you shirk, and shall find you if you hide. Begone, and trouble these lands no longer!”

Gwyntus stood in the air like a shepherd after fighting off a wild strider, watching as Dil’gud scampered away with his scaly tail coiled around himself and his stone hands pawing at the air as he hastened to follow the horse’s injunction. There would be other Wild Winds to battle and return to their proper place in the Vindur barn, but not until after he finished his initial aim.

He smiled at the satyrfish winds, sweeping his arm wide to indicate their safe passage to the west and south. No longer afraid of the errant Dil’gud, they stampeded forward, bearing with them a cold front and long curtains of rain. Gwyntus followed, eager to be present when his friends received the bounty of his success.

¶ß

Kibou’s audience was growing restive, now that the climax had been reached, so he wasted no time in drawing the threads of his tale together. He rattled his tail bells, gently at first, tentatively, but with growing ardor. “When the rains came to Eret, there was dancing in the street, elders and children alike splashing in the mud and throwing their heads up to receive the blessed water. But no matter how he gestured or called, they did not see Gwyntus. Neither sound nor touch bridged the gap between mortal and anima.

“He’d known that he might never return and he was grateful that at least he could see the fruits of his labor, his sacrifice. So he straightened his shoulders and leapt off in his boots to finish collecting the remaining Wild Winds from the world. By the time he was done, Eret was again a green and fertile region, and his house had moldered, falling down until it was little more than a grass-covered hummock.”

The bells stilled and Kibou stood proudly. “There was no going back for the farmer, so instead he went forward. His long travels across the world had given him time to think, and so when he returned to the Vindur palace it was with a plan. Three of the brothers would remain on guard, while the fourth would traverse the skies for his season—Lanwyn in the spring, Hafpanas in the summer, Raugdref in the autumn, and Gwyntus himself in the winter—ensuring that the Winds, both Wild and Tame, performed their various functions, bringing rain and sun, blowing seeds and sand, without interruption. And so the farmer invented weather, and saved not only his village, but our world, from the mischief of the Wild Winds. Thus my story is finished, it has returned whence it came.”

After a moment of silence, for so all stories begin and end, the audience applauded and the lung took his bows, using his tail bells to mimic and accentuate the sound of coins being tossed into the broad-brimmed hat spread on the stone pavement before his platform. And then, like audiences across the whole of Talamhir, they departed in ones and twos, attention drawn by other enticements, other duties.

All but one.

The horse stood where he had been standing, staring at the dragon as he removed the strap of bells from his tail and gathered up his hatful of coins. Kibou poured the money—mostly bronze circles, with a few silver squares and a single golden triangle—into his strongbox, then donned the hat with a flourish. Turning back to the remaining auditor, he spoke. “Hello good sir, how might I assist you this fine morning?” He had dealt with his share of hecklers and opinionated listeners before: those who lost their manners or their sense with a tankard or two in their skins, or the dangerous simpletons who believed that to change a story changed the history it reflected, or angry souls who just didn’t like his tone. But he wasn’t prepared for what this one had to say.

The white horse blinked at him and spoke, his voice unsteady as though he were unfamiliar with its use. “Why,” he asked haltingly, “do you tell that story? Why is there a celebration here?”

Kibou stared at the handsome stranger. There was intelligence behind the confusion of those dark eyes, and tracks in the hide indicative of unheeded tears, but also a steadiness to the way he planted his hooves; no drunkard imbecile here. “My friend, you must be new in town! This is the festival of Gwyntus Vindur, to celebrate the Westnorth Wind and the changing of the season. As for the story, that was his history, the tale of how he became what he is. In legend, at least.” Kibou paused, looking the horse over. Inspiration struck, and he tried his hand: “Good sir, do you have any pressing business for the next hour or two?” The white horse blinked again, his brows furrowed, but gave a tentative shake of his heavy head. “No? Then come with me.”

Moving with alacrity—lest his new friend lose heart or recall some prior engagement—he bundled up his cart, folding and securing the floorboards and the legs that supported them, and draping a protective fabric across the painted decorations. He trundled it swiftly through the crowding streets and over the bustling bridges of Sashim, depositing it at the hostelry where he was staying, escorting the bewildered horse all the while, until they reached the Commerce Guildhall. It was common knowledge that a prize awaited anyone who would volunteer to be the Gwyntus in the festival, and a finder’s fee as well. Kibou was not one to sneeze at luck, nor could he ignore when such a prize was dropped in his lap.

He explained this to the stallion as he led the way up to the ornately-carved doors. He presented his find, first to the entrance guard, then to secretaries and clerks of increasing importance. The guildmembers had a dozen questions for the horse, primarily concerning his availability and fitness for the role, and confirming that Kibou was indeed the one who convinced him to volunteer.

A functionary provided a diaphanous white robe, leaving the horse’s boots but taking his homespun tunic and breeches with the promise that they would be waiting (along with the promised rewards) on his return from the prescribed perambulation of the city. “So, you go to the Pharos of Perception and, as proof of your circuit, bring back the staff. You know they say it fell from the sky a hundred years ago? I personally doubt it, since it looks just like a piece of old wood. It probably just fell from a roof or balcony or something. Those old folks are so superstitious, don’t you think? Anyway, it should take you about an hour to get to the Pharos and another to get back, but of course you’ll be well-paid. And no need for makeup this year,” the vixen remarked with relief as she folded the still-warm clothes and curtsied herself out, leaving an echoing silence in her wake.

The room, paneled with paintings of allegorical scenes in the Kalaptrian style, seemed chill and overlarge after the departure off the bustling guildwoman, but there was no cause for the two men to linger either: the sooner they departed, the sooner they’d be able to return. Kibou said as much to his serendipitous companion, but the horse was reticent.

“I do not know what to do, what is expected,” he said slowly, lifting his arms and wafting the veil of fabric that draped around him like a winding sheet. He seemed deflated and weak, despite the limbs and torso that bore a laborer’s sturdy physique.

“I’ll go with you! Sashim is easy enough for a local to get lost in, let alone a visitor. But I know my way around, and if we do get lost, I can always float up and get my bearings from one landmark or other.” His feet lifted from the air as he said this, floating with a little of the air magic innate to his race. This convinced the horse as much as it surprised him, and he allowed himself to be dragged back to the guildhall’s main entrance without any resistance.

But Kibou paused before the vast doors and turned to his companion. “What shall I call you? I can’t believe I haven’t asked yet. How rude of me.” He bowed his apology.

The horse looked down at himself, the costume he wore and the role he’d been roped into. “I suppose…Gwyntus would do.”

“Well, at least that’ll be easy to remember.” The lung replied with a wry grin, sticking out his hand. “Gwyntus, I am Kibou the Captivating, and it’s a pleasure to meet you.”

The horse merely smiled and shook the dragon’s hand.

A cheer emerged from the mingling crowd on seeing the arrival of the day’s hero, and almost immediately a throng of children ran up to him. Some carried kites, others were dressed up as leaves and cherry blossoms. The newly-minted Gwyntus looked at his handler with confusion, and Kibou grinned his encouragement. “Go on,” he whispered, “what wind doesn’t dance with leaves and kites, eh?”

The horse snorted but allowed himself to be grasped by the tiny eager hands, pulled this way and that by the noisy crowd of blossoms and leaves. The irony of a wind spirit being thus controlled was not lost on the audience, and the cheers and laughter grew when someone began to drum out a tattoo on the bottom of a copper pot. Soon the horse found his footing and the crowd of youngsters fell in step behind him, a joyfully chaotic caravan winding among shop stalls and pillars.

At some point Kibou had purchased a handful of mint leaves from an herb vendor and pressed them into his ward’s hand. “Chew these,” he commanded as he danced in a circle with the horse, “and blow minty kisses at the back of people’s necks.”

“But…won’t that be an affront?”

“Ordinarily, perhaps, but you’re the winter wind: you’re supposed to be chilly.”

So he added this to his wind spirit repertoire, growing in confidence. As he progressed through an arch and over a bridge, some of the children fell away—likely under orders not to stray too far afield—but they were replaced by more as he made his way through the city. When he reached one of Sashim’s hexagonal squares, however—very much like the one where he first met the bard—he was forced to stop.

The adults had taken their places in the ritual, their enthusiasm likely spurred by swift-flying rumor of how good this year’s Gwyntus was. So they had gathered, standing just inside the entrance to the plaza. Some wore outlandish costumes and others bore poles atop which were mounted puppets, grotesque to the point of silliness. Looking like they’d crept from the marginalia of a Jipoe manuscript, these were intended—Kibou explained quickly—to represent the Wild Winds and yokai defeated by the real Gwyntus Vindur. The horse would need to dance them into submission, twirling dancers and puppeteers alike until they grew dizzy and relented.

With increasing energy he leapt and bounded around the quarry intent on barring his progress, just like pieces of the “Gwyntus and the Wild Winds” game. There was a joy in his movements, as though some subtle weariness had been lifted from his shoulders.

And so they wended their way across the city. Musicians—both impromptu and professional—added varied their cadences to the parades and mock battles, and the horse (especially when trailed by a train of giggling children) snuck up behind unwary folks to blow chills down their spines. Occasionally winsome maids or handsome lads would try and ensnare him in their arms, hoping for a more lascivious kiss, but he dodged their embraces as easily as the wind slips through a sieve.

Instead, when the music and the spirit moved him, he would grab one of Kibou’s hands and twirl him around, his formerly-impassive face softening by degrees until he was bestowing broad buck-toothed grins on the children who swirled in his wake, and on the lung who kept pace with him through each corridor and courtyard. There was a tenderness in those wintry eyes, a gentleness in the strong snowy-hided hands. In all the noise of music and laughter, the cheers and gasps as he fought the colorful Wild Winds, there was no chance to talk. Nor would they have had the breath to form words through grinning lips. By the time they reached the eastnorthern-most corner of the city, the horse had fully accepted his ceremonial role, his hoofsteps so light as he spun and pranced that he seemed to be floating like the mythical winddogs of Tarnby, or like the lung himself.

Kibou, succumbing to the contagion of the mock anima’s joy, found himself constantly surprised: first with how well the horse fit the role he’d been shoehorned, then with how well the role seemed to fit him, and finally by the other man’s boundless energy.

It felt like any time his own vigor was fading, all the dragon had to do was look at the horse. Heart pounding, Kibou the Captivating let himself be spun around the hexagonal plazas, a whirling dust devil to attack the Wild Winds’ flanks.He gathered his own trailing chain of costumed children and led them in a merry promenade, weaving in and out of the line behind Gwyntus, like an impromptu folk dance. And each time the two men drew near, his eyes met the horse’s, their hands grasped, and they twirled in their own little eddy for a moment, before rejoining the battle or conga they had temporarily forgotten.

And now they stood below the shadow of the massive crystal-topped tower that marked the climax of their journey: the Pharos of Perception.

They crossed the long bridge in silence as the waters rushed by beneath them; the crowd of waiting onlookers stood in a reverent hush, for this was the most solemn point of the allegorical progression across the city. The arched passage before them drilled through the tower’s base, which supported the spire of Tenobrian crystal whose light shone out every night and each dark day to guide ships to safe harbor. With the lung as his own guide, the horse strode into the darkness. The passageway let out on a broad balcony, the lookout beneath the lighthouse.

With the ocean-like expanse of the Dragon’s Bay arrayed behind her, a motionless lioness stood swathed in purple and with a snake-headed belt of silver clasped about her narrow waist. Kibou couldn’t tell if she looked bored, or if she was just trying ineffectively to put on an air of detached inevitability, but regardless of her acting skill, the next step was clear. “She represents Destiny,” he whispered to the horse. “Go up to her and kneel, accepting your fate like in the story, and she’ll give you the staff.”

The horse snorted, instinctively bridling at the thought of submitting to anyone, but he quickly mastered his emotions and strode forward, leaving Kibou in the shade of the passage. The noon sun lit up the robes of Gwyntus so even his hide seemed to glow, or perhaps it was just the moisture in the air or some effect of the crystal above. As he knelt, the darkness of the lioness’s garment seemed all the more dramatic, a spot of violet night in the blazing day, a weighty line begirt by silver. Destiny lifted up the staff, resting on her outstretched palms, a horizontal of soft fleshy red which she then lowered before the horse’s nose. The hush of the crowd peering through the arch seemed to grow even more breathless as they jostled silently for a better view of the crucial moment.

Wordlessly, he took the staff. The very air seemed to hold its breath at that moment, and Gwyntus flexed his fingers as though seeking a familiar grip on the wooden length. He stood, following her gesture to return through the arch, back to the world and to his duties. With Kibou following in his wake, he passed beneath the tower and reemerged onto the bridge, instinctively holding the staff aloft. The crowd cheered and a band began to play a triumphal march, buoying his steps as he passed through the gauntlet of applause and adulation. Kibou looked at the squared shoulders, the tall stance of the horse before him; it was easy to forget that the celebrants were lauding an idea, a symbol, rather than anything the horse had done himself.

Still, it was good to see the originally taciturn man smiling and waving, really wrapping himself up in the role. Especially now that his role is nearly done, Kibou thought as he guided him away from the Pharos, the lioness, and the crowd. Ostensibly, there were still other courtyards to “cleanse” of the wild winds, other throngs of children to lead in his merry dance, as they completed the cycle from the crystalline lighthouse in the eastnorth corner back to the Commerce Guildhouse in the eastsouth corner, where the parade had begun. But many years ago this second part of the circuit began to be neglected: in a reversal of the legend, the staff-giving marked the climax of the ceremony, and given how short the remaining leg was—and how tired most Gwyntus volunteers were be after traversing three-quarters of the city—the celebrants increasingly poured their energies into the first part.

So now the two had only a quiet walk back to the Guildhouse before the horse could hand in his garments and they could both get paid. Kibou looked at the staff: it had been polished by the use of many hands, with a simple twist carved into the grip, a few lingering branch stumps on the head, and a fire-hardened tip. In the horse’s grip it seemed almost an extension of his body, as though those many hands had all been his. The Guild’s vixen had indicated that it was kept with the robes of the Destiny actress and the Gwyntus actor, a tidy bundle of everything needed on this one day of the year, but what if, before that…

Suddenly, they’d stopped walking.

The horse was standing at the edge of the street, propped up on the staff. The wind blew out of the eastnorth, through the city massed at their heels, and wafted the smell of the noodle bar immediately behind them out across the bay and to the world beyond. Kibou stepped close, placing a hand on the strong, fabric-swathed forearm; perhaps his friend was weary, or hungry, after such a long and energetic cavort, but when the ice-blue eyes looked down and into his, there were tears frosting their edges.

“How many times have I wandered through this city?” he asked aloud. “How many winters have I spent in other places? How many stories have I heard? And yet today, like an astral conjunction, all three have come together; today I remember.” He held the staff, fingers seeming almost to caress it. “I lost this, many years ago. I was battling what I thought was a particularly strong Wild Wind, or perhaps some other yokai, high over the city.” He turned and pointed back at the towers and windmills behind them. “It was no mere Wind I fought that day, but a genie.”

Kibou had to silence an involuntary snort: everyone knew that genies were as mythical as the Vindur Brothers. But the horse clearly believed otherwise, so the lung kept his mouth shut.

“He bested me,” the temporary Gwyntus continued, “knocking my staff from my hands, and with it my memory. Not all at once, you see, not so I’d notice it, but fading over time, until not even my name remained to me.”

The lung listened, his mustache tendrils quivering with premonition; he was loath to interrupt the other man, to damage the fragile petals of blooming memory, but he had to know: perhaps this horse was just some actor, hired by the Commerce Guild years ago, who’d lost his memory in the performance of the annual ritual? Or perhaps…but no, that would have stretched any imagination. As a teller of tall tales, Kibou prided himself on his grounded worldview. Wind spirits and yokai indeed. But he could still see the perplexity in the flagging ears, the stiff shoulders; regardless of the truth ultimately arrived at, this was still a sentient in distress. He would be remiss if he didn’t listen with compassion, providing and anchor to reality as his companion probed the depths of his shattered memory.

“That is why I listened to your story with such attention,” the horse was explaining. “Most of the details differed—“

“Differed? But that’s the version I’ve told and retold every festival for years,” the performer couldn’t hold back his own confusion.

“The Wind House was no great palace, just a hut in the snow, without even a hillock to protect it—let alone the vast wall you described—and the other Brothers are more apt to argue than agree, which is how the Wild Winds escaped in the first place. I never met the Speaking Wind, neither on first awakening there nor in all my travels; either she hides in caves or (more likely) she doesn’t exist at all, except as a story to explain echoes and warn against the dangers of spelunking. And my hide was brown…” he paused his enumeration to meet the dragon’s eyes. “But if I’m being honest, which I am, I like your version better: it’s more poetic.”

He continued, “So, even with those differences, there yet remained enough truth to light the candle of my memory. And with every tiny spark, the flame grew brighter. These robes, the play-battles with the Wild Wind puppets, this staff; each one played its part and now I feel whole again. Now I feel that I am me once more.”

Kibou looked at this man and saw the resolute pose, the stalwart solidity of his neck and shoulders, the sturdy boots that seemed to be more than mere leather, all counterpoints to the way the robes flowed fluidly around his body in the wind. He also noticed for the first time that there was a hollowness in that strong back, the wind making a circular depression in the fabric like a sideways, inverted dome. “And…who are you?” he stuttered, knowing the answer.

“I am Gwyntus Vindur, the Eastnorth Wind.” The white horse turned to face the lung, cupping the side of his jaw in tender fingers. “And you have awakened me.”

The touch was cooling, but with a heat deep within those fingers long ago grown stiff and strong from fruitless years in the fields. The lung couldn’t resist as his neck bent and pressed his cheek into the waiting palm. There was no denying the attractiveness of the horse, let alone the fascinating possibilities he offered to a teller of tales, whether he be truly an ancient and powerful anima, or merely a gentle madman. It took Kibou a moment to realize that they now hovered a few cubits above the stony street. While the magic innate to his race meant that such flight wasn’t an unusual experience for the lung, what was unusual was that this was not of his doing at all.

The flowing white robes seemed to trail longer than they had just moments ago, forming a swirling vortex around and beneath the two men. People passed by on the street, clutching hats and capes against the swelling breeze, but they noticed neither the lung nor the horse.

The wind caressed Kibou’s body, only the gusts were Gwyntus’ fingers, stroking the dragon’s mane, toying with his mustaches. The breath from the horse’s mighty nostrils blew against the scales of his neck, every breath a new puff of wind, frosted and fresh with the lingering scent of mint leaves. Everywhere at once now, the anima swirled, bearing a veil of green and brown oak leaves blown from some sacred tree in the city, dancing with more fervor than the wildest child had that day, and with all the energy and none of the malice of the feigned Wild Winds.

“Gwyntus,” Kibou moaned as his body arched, back and tail pressing against the impossibly solid wind as though he were held by a giant’s hand, his own hands reaching out to grab hold of something, anything, and finding fingers to intertwine with his own. Cool breath and warm body pulled near, a powerful chest blocking the light—apart from the full-moon hole that glowed through robes, themselves now more than simple fabric—as the former farmer’s muscular neck leaned in, hide against scale.

Kibou couldn’t resist as his mouth fell open, his lips parted by the soft dry touch of Gwyntus’ kiss, like a granite statue brought to life. But the tongue that slipped between was as hot and vital as any man’s, and the hand that held his shoulders and the arm around his back were stronger than iron. Fetlocks danced against the dragon’s ankles in the breeze that surrounded them both, wrapping them in a blanket of opaque air. Storyteller and story made one for a moment of shared heat and shared breath. It was not love, not yet, but Kibou would have been lying to himself if he denied the hope of what it might yet be.

So when Gwyntus Vindur pulled back, he saw tears in the dragon’s eyes, and brushed them aside with a gentle gust that made Kibou blink and turn his head. When the mortal looked back, there was a weight to his gaze. “You are real. I…still almost can’t believe…but here you are. ‘Thus my story is finished, it has returned whence it came.’” he said, quoting himself with a wry smile. And he caressed the horse’s head, surprising him with the gentleness of claws currying through his mane. “I want to know…”

“And I want to tell you, everything.”

¶ß

The winds were fierce that night, but with an unusual gentleness, as though the wind spirits—for those who believed in such things—were being playful, and many saw waterspouts rise and fall back harmlessly in the wide Dragon’s Bay. The Commerce Guild was surprised that their volunteer didn’t return to claim his fee, nor the dragon who had found him, but the promised money would more than cover the loss of staff and robes, so there were no complaints.

The weather, too, after that night was for a long time afterwards not the cause of complaint: it seemed every waterborne vessel had a following wind, while airships felt not a gust of breeze as they took off and landed. The faithful (and superstitious) chalked it up to the skill and energy of the horse who had played Gwyntus, for the spirits had finally been appeased. Of course, others merely pointed to the weather sages who predicted fair weather, based on the movements of their barometers and other gauges; a totally natural phenomenon.

¶ß

“I still can’t believe how good he was,” a lioness said to her coworker as she folded purple garments into a half-empty box, placing a silver belt on top of the fabric. “I mean, I half believed I was Destiny.”

“Watching that performance,” the lynx replied as they walked outside to fetch dinner, “I felt like a cub again. You could almost feel the wind following behind him”

“That was the best Gwyntus I can remember,” said a zebra in line at the handpies cart behind them. “It’s like he never got tired, not once!”

“My dad said next year I can be a Wild Wind too,” announced a little orc with cherry blossom ribbons in her ponytail. “I hope the Gwyntus comes back then.”

> [¶ß\ >

10,029 words, please view PDF for full text, proper formatting, and illustrations (also visible here: https://www.furaffinity.net/view/53471833 )

---

“It just won’t be the same this year,” opined a lynx, tugging at a tufted ear while waiting for his turn at the market stall.

“I’d volunteer,” offered an apologetic-looking zebra, “but the paint they used last time made me break out in a rash.”

A rhino in line behind them added, “I can’t believe there isn’t a white horse in all of Sashim.” He paused, stroking a contemplative horn, “At least, none as will volunteer, if only for the weather.” Unspoken was the commonly held superstition that a well-performed ceremony would settle the winds and waves. And the always looming specter of possibility: that if conditions didn’t improve, the traders and fishers on whom the city depended would find friendlier harbors, leaving Sashim a ghost to be swallowed up by its own rebellious bay.

“I heard that the real Gwyntus hasn’t been seen in a generation,” said a wistful old woman, “Or was it a century? I can’t remember. That’s why the weather has been so fickle, and why it’s so important to have this ceremony: to remind the winds of their master.”

“Oh yes, grandmother,” her hearers agreed respectfully, though few actually believed that such an enjoyable event (irritating makeup aside) could actually be the cause of atmospheric change.

¶ß

The conversations all throughout the “city on the sea” were going in much the same tack. The Sashim Commerce Guild—a guild of guilds, as it were, whose membership was comprised of representatives elected from the Guild of Merchants, the Scribblers’ Guild, the Association of Costermongers, and similar professional organizations—was wringing its collective hands with worry. The sole volunteer for the day’s centerpiece role had come down with Green Gore, and nobody blamed the white mare for bowing out. Bedridden and vomiting from contaminated water (likely from a stagnant cistern, suggested a wag from the Laborers’ Guild; but everyone knew that he had aspirations to be Commissioner of Works, and therefore took every opportunity to pin fault on the current officer), there was no way she could have donned the requisite costume to prance about the bridges and hexagonal basalt pillars of Sashim, let alone perform the other expected duties.

So now, like a harvest festival with no harvest, the Gwyntus Vindur celebration was set to begin without Gwyntus Vindur himself. Across the city, horses, donkeys, and zebras repeated similar excuses to friends and strangers alike; after all, the role was hardly mandatory, and the celebration would go on with or without the deity it honored.

¶ß

In one of the city’s many six-sided squares—with open water on one side, a cistern in the center, and backed by the colonnaded façade of a Temple to Concord—and beneath the spidery shade of an ornamental oak bereft of leaves, a bard had set up shop. The ornate painting of his handcart-cum-podium proclaimed him to be “Kibou the Captivating,” who had performed in Gulporte and Bayard and Midsune. The lung dragon began with the usual assortment of seasonal songs, their familiar words and tunes drawing in passersby: “My Love’s Cheeks are Redwinter Berries,” “How Cold the Lonely Hearth,” and the humorous local favorite “My Clock is Frozen, How About Yours?” His pearly scales and mint-green mane attracted attention nearly as much as his buttery voice, so when a suitably large crowd had encircled him, he stood, turning the slow movement of legs stiff from long sitting into a graceful unfolding of stocky limbs and long spine. A solid strum across the strings of his death’s-head lute caught the ear of any stragglers and alerted all to the fact that a story was about to begin.

Chill sunlight glinted warmly off the gold threads that hemmed his robe and obi, and gold were the bells strapped to his tail. Kibou rattled them with a whipcrack undulation of its length, shushing any chatterboxes and giving his words space to expand.

“I sing,” he began, (though the tale was prose and not poetry) “of wind and of rain, of soil and root and crop, of the end of some things and the beginning of others.” The lute reverberated as his fingers nimbly plucked a gentle scale.

“In the old days, before our world became what it is, balance was unknown—“ a minor chord, “—there was uncertainty—“ a sharper discordant tone pair “—and loss.” The lung’s tail, with its burden of bells, shook like a mourner’s sistrum. “In short, my tale is of the Invention of Weather.” So perked were the listeners’ ears that not one took notice of an extra figure in their midst, a tall white horse of statuesque musculature and bearing. He listened with curiosity, as though he’d never heard the famous legend before, an occasional breeze rippling his unadorned tunic.

A subtle shift to the twitching of Kibou’s tail altered the bells’ tintinnabulation to match the story’s proper beginning:

¶ß

The weak west wind hissing through the branches of the dying trees made a sound like a cloudburst, an illusory downpour. The taunting noise was alien to the children who heard it, and a fading memory to the older folks who looked up at the iron skies with forlorn hope. No matter how they wished or prayed, there simply…

…was…

…no…

rain.

The aquifers were running dry, and the wells they fed—the wells that farmer and herder and householder alike depended on—now gave forth little more than mud. Cisterns and rain barrels held only dust, dry air, and the nests and carapaces of countless generations of insects. Eret, that town we now all know as the greengrocer of our nation, was dying.

The town elders held council in the central warehouse: after hearing several proposals (sinking more wells, the purification of swamp water, sacrifices to various gods, or even the search for a spell to draw water from the air itself) the decision was made to hire a tanker cart to haul water from the rivers springing in the Karal Range to the south. But after so many fruitless years, the village’s meager remaining savings wouldn’t suffice for more than one trip of what was effectively a big tavern barrel on wheels. There would hardly be enough water for one farm, let alone the entire township.

Then a lone farmer stood from the back of the assembled men and women. He ran a hand through his dark black mane, as though trying to calm his nerves, his hide as dull and dusty as everyone else’s in the town’s vast and empty warehouse. The cavernous space fell silent as he cleared his throat. “It seems to me,” he said, measuring his words like bushels of grain, “that our only option is to seek help of a less…ordinary sort.”

“But we tried prayers,” the replies came from all sides, “and sacrifices, and ceremonies, and our parents hired that charlatan of a wizard who said he could magik water out of stones.”

“Aye. But we have not gone in person to present our pleas directly.” He held up his hands—rough from long and futile labors—to forestall any protests. “My farm is dead, my crops withered beyond rescue. Even if there were water enough in a tanker cart to saturate my fields, it would not come in time to save them. I will take what food I have left and go north.”

“To the Wind House?” exclaimed the familiar voices around him, marveling at the audacity of the suggestion. He might as well have suggested that he would seek out the ancient geniuses and genies of fallen Nordant, or travel across the seas to the Forbidden Jungle of Klodrai for a solution to their collective plight.

“Indeed. If I perish in the attempt, then it will be no different from my fate if I remain,” he said, standing resolute against the rising tide of argument. “And if I do succeed…” His open palms said more than his simple words could have, and quelled all further protest.

The elders agreed: the farmer would embark on his journey north, as others would go south to continue the original plan. One way or the other, the farms must have water; two seeds in the furrow were better than one. So the farmer gathered his meager provisions—including donations of journeycake and other way-food—wrapped puttees around his hocks, and left his village without another look back. If he failed—even if he succeeded—he was not likely to see his home again, but being a practical man he knew what had to be done, regardless of the outcome for himself.

He trudged along for league upon league, past dried-out forests and flooded deserts, villages abandoned to time, and various other signs of the disorder of the world. The sun seemed to bounce from one horizon to the next, sometimes westward, sometimes eastward, fast and slow, while the winds buffeted him before and behind, tugging at tail and mane, cloak and pack. “Stop this madness!” he cried, holding onto his clothes lest they be rent from his body by the impish winds, using his cedarwood staff as a prop against being overturned.

None answered his plea.

The horizon stretched before him now, flat and featureless, with flurries of dust or powdery ancient snow—he couldn’t tell which—kicked up by the same whirling gusts that threatened to spin him around until he had utterly lost his direction. There were no mountains, not even the husk of a dead tree to fix his eye on as a waypoint, and in those ancient days before compass and astrolabe he had only the crazy dance of sun and stars to indicate his goal. Stolidly he trudged on.

A vast wall rose up ahead of him, as though the ground had been carved away by a giant’s cakeslice. It seemed to stretch on forever, with neither break nor deviation for as far as he could see in either direction. There were no hand-holds, neither grooves nor crevices to fit his hooves into, no stair carved up nor ladder dangling down. He sank to his knees, shouting wordlessly with his despair: he had one, maybe two days of provisions remaining, and little enough strength to consume them, let alone decide on a direction of wall and then follow it in the baseless hope that it would at some point end.

“I’m sorry,” he wept, his voice hoarse with the cold, “I failed.” The foolish certainty of his success no longer bolstered him no longer shielded him from the hardships of his journey, the deprivations of so many long years without rain. What good was it to eat the remaining morsel of stale bread, drink the last swallow of murky water, to stay alive for a few days more, when there was no hope for salvation, neither for himself nor for his village. Perhaps the tanker cart would suffice to rescue them.

He fainted dead away.

¶ß

The lung ceased his tale, the bells on his tail preternaturally still as he looked about his audience. They all leaned forward where they stood or sat, ears open to catch his next word, eyes wide but unseeing, so absorbed were they in the picture Kibou had been painting in each of their minds.

He took a languid pull from his waterskin, the subtle infusion of sage, mint, and chamomile tingeing the taste and soothing his throat. Just as a fiddler might rosin her bow mid-performance, Kibou the Captivating had long ago learned the importance of tending to his own primary instrument. Filling his mouth with another swig, he let his fingers dance across his lute’s strings, calling up a mysterious theme as his tail shook off its stillness and added a cascade of sound, as though the listeners were enveloped by the leading edge of an approaching blizzard.

The horse alone stood unmoved, his brow furrowed and hand stroking his chin as though lost in thought, or trying to recall an elusive memory. Perhaps he’d heard the story differently in his village, Kibou surmised, shrugging off the one auditor who hadn’t thus far fallen under his spell. But there was the rest of the tale yet untold, and he’d never left an audience unsatisfied. They don’t call me “the Captivating” for nothing.

The strummed melody shifted again, weaving strains from different lullabies into a soothing tapestry of familiar sounds. He let the last trickle of cold herbal water caress his throat, then resumed the story. “The horse awoke in a magnificent hall, on a bed of cloud covered by sheets of mist. At his stirring, he heard ghostly footsteps dancing around him,” the tail rattled lightly, so that only the smallest of the bells tinkled.

¶ß

“Hello?” he cried weakly, then succumbed to a coughing fit; blackness crept along the corners of his vision and he fell back on the cumulus pillows, exhausted. A few moments of focusing on his breath, on the pulse throbbing through his ears, the weary stiffness of his legs, helped to calm him, ground him in reality…and help him ignore the growing ache in his chest.

“Hello? Is someone there?” he asked again in a gentler intonation, hearing wordless whispers in the corners of the cavernous room.

“They’re afraid of you,” intoned a mournful voice from the side of his bed.

The farmer looked down and saw a tiny figure, a lithe vixen swathed in fog who stood barely taller than his hock, the hair of her beautiful human face streaming down to mix with her diaphanous garment. “Who are you, little one?”

“I am the speaking wind, I hid in caves and forests and lured travelers to their doom by sounding like a familiar voice.”

The horse recoiled and tucked his legs up under his cloudy blanket. He had heard the stories of this particular yokai, who was just one of many spirits the mortals of his era had to fear. “You’ve kidnapped me!”

“No,” she said, tears spangling her ebony locks and a blush coloring the pale skin of her face. “I am myself a captive in this place. In penance for my victims, I now must serve as steward and majordomo. My masters bid me to bring you to them once you had awakened.”

“Then those other voices…?”

“Those are the Tame Winds. They stay within the palace here, skittish as pet mice, tending to chores. I am in charge of them—which is penance enough in itself—and must ensure they perform their duties. While they stand guard, the Brothers placed the Tame Winds here to protect them from the Wild Winds.”

Though his head was swimming with questions, the farmer slid from the bed and stood shakily on his hooves. The staff which had helped him to cross the leagues from Eret was propped up beside the bed, its familiar grain welcome under his fingers as he picked it up to aid his unsteady steps. Perhaps by speaking with these Brothers he might get a straight answer. A flickering hope raised its tentative flame in his breast: perhaps his mission…but no, he couldn’t allow himself to complete that thought, even in the secret depths of his heart, lest the breath of excitement snuff it out.

The irony was not lost on him as he followed the Speaking Wind through the echoing, whispering halls, then down a spiral stair and into a vast barn-like space. It was shaped like a triangle, with a vast archway set into the center of each wall. Three men, horses all, stood guard, each one filling the archway where he was stationed. Perhaps it was a trick of the light, but as the farmer looked around, he noticed a brightness shining through them where brightness ought not to be. It was as though they had a hole cut through them, one’s belly, another’s face, and the third’s forehead each showed the sky beyond.

His courage failed and he stopped on the final step, one hoof raised above the barn’s floor. The guards didn’t move, with only the rise and fall of their shoulders and the swell of their backs to show that they were alive. After a moment, the farmer relaxed slightly, and his leg shifted, lowering, until his hooftip brushed the packed dirt.

The horses spun around as swiftly as whirligigs, staring at the intruder, their faces impassive and inscrutable. The farmer quailed, falling back against the stairs, his tunic fluttering as the minuscule yokai rushed over his body. “My lords,” the fox with a human’s face said, bowing low as her tail swept the ground, “this is the visitor we found outside the walls. He has been restored to health and begs leave of an audience with yourselves.”

They looked from one to the other, as though uncertain how to proceed. Finally one of the trio stepped forward, and as though perspective had reversed its laws, as he drew nearer he lost his fearsome aspect; by the time he stood before his guest, they were of the same stature. “I feared you might never awake,” the sorrel horse said, though the farmer couldn’t see how: the horse had no muzzle, neither lips nor tongue, but only a circular hole beneath his eyes, punched straight back through to his mane. This didn’t seem to affect the horse, who continued: “When our half-tame winds—the ones brave enough to patrol the perimeter of our palace—found you, they thought you were an ice statue left by zealots or carved by the Wild Winds.”

The farmer laughed, “But since when has a black horse looked like ice?”

“Black? Are you certain?”

The farmer held out his arm as proof, pulling up the tunic’s sleeve for good measure, then stared at the hide thus revealed: it was as white as the driven snow, pearly as frost and soft as laundered linen. He ran a hand across it, roughing it up with his nails in the hope that black roots might be revealed, but even the skin beneath was white. He’d been bleached by the sun and the frost, drained of all hue. He fell back against the bulk of the stairs, dropping his staff and clutching at his chest. His journey had cost him so much already, and now even the color of his hide had been sacrificed, stolen away by the Northern Wastes.

But the faceless horse smiled—or seemed to, from the way his missing cheeks squished the corners of his eyes—and turned to the farmer, holding out a hand to lift him to his hooves once more. “What quest has brought you to our halls?”

“My name is Gwyntus of Eret, and I have come to beg assistance for my village. Your steward,” he nodded at the diminutive figure, “mentioned Tame Winds and Wild Winds, so I hope that my pleas may fall on the right ears. Do you three control the winds of the world?”

“Yes,” the horse said, though his reddish ears canted back as though the word didn’t quite do justice to reality.

“Then you can help me! My village—for we are farmers all—is dying; we have had no rain in many long years, not since I was a foal myself. Our aquifers and wells are dry, our reservoirs long since emptied, and all nearby rivers are nothing but stony grooves in the land. Have we caused you anger through some misdeed, some impious word? Have we omitted some act of supplication? Please, tell me how we have offended, that I might make it right.”

“Eret, you said?” He toyed with the lavender broom he carried in place of a guardsman’s sword. “No,” he finally conceded, “your drought cannot be of our manufacture, for we control the winds, not the waters.” Then the sorrel horse looked at his brothers, saw the nods and downcast eyes. He cleared his throat. “Unless…I wonder: in your village, are the winds fitful or strong? Do they come from one direction or many?”

“Fitful, and from all directions.I remember in my youth that each season would have its winds, steady and strong enough to fly the heaviest kite, but now they only stir up dustwhirls and throw grit in our eyes.”

The sorrel horse blustered through nonexistent lips. “Then I regret to tell you that your plight is indeed our doing—though no fault of yours, nor your village’s.” He added, placing a hand on his guest’s shoulder. The warmth and tenderness of his contrition made the farmer’s eyes well up with tears, tears that frosted into snowflakes as his eyelashes batted them away.

“If only,” the sorrel continued, “we could leave our posts, we might remedy this problem.”

“But why? Why can’t you?” the farmer asked, staring at the glittering ice stars his own eyes had created, a miniature snow drift in the whitened hairs of his palm.

¶ß

The lute strings, held against the instrument’s neck, produced brittle-sounding high notes: the sound of crystalline tears delicately shattering. Kibou looked around his audience, tense faces expressing the same desperation as the protagonist, the more emotionally-sympathetic among them with non-snowflake tears in their own eyes. And among them stood the horse, motionless, eyes unseeing, staring not at the lung minstrel but through him. An odd one, that, Kibou thought, but there was story yet to tell.

“We got…distracted with a dice game,” he said in the voice of the faceless sorrel horse, rattling his tail like the wooden cubes in a bamboo cup: taka-taka, taka-taka, skoosh as the imagined dice scattered across a table, then taka-taka again for the next hand. “We were tasked with guarding the Wild Winds here, and so engrossed were we in the diversion that we each thought one of the others was still standing guard.”

Some of the older heads in the audience shook ruefully, knowing first-hand, perhaps, the dangers of gaming, and certainly of immoderate distraction from one’s duties. One or two of the youngest faces stared horror struck: could a simple game of dice have thrown the world into such disorder? Kibou smiled to himself, proud that he could weave some morsels of instruction into his entertainment. The lute strings cascaded mournfully as the horse continued his explanation.

¶ß

“But of course there are only three of us, and three doors to guard, and three filled seats at the dice table. Because of our negligence, all the Wild Winds escaped out into the world, so now we stand here, guarding our empty barn in case they come back.”

“You are waiting, here,” the farmer repeated slowly, dumbstruck, “guarding an empty barn, in the hope that these Wild Winds will return to their captivity? On their own?”

“What else can we do?”