A humble tea-seller in Tenobrius dies, and his youngest son inherits a black and white kimono with magical powers. By being dutiful, resolute, and open-eyed, he unlocks these powers, which enable him to save his city and make his fortune.

8,349 words, please view PDF for full text and proper formatting.

---

Back in the days when each city was a kingdom to itself, there lived in Tenobrius a chaiwala. This donkey's eldest daughter looked so much like his wife that he always smiled when he saw her. His second child was a polar bear, adopted when the cub's parents were lost at sea. His third child was a fox, likewise adopted and soon the most-beloved of all the donkey's children.

This young fox—Ebsin by name—had a true heart and an earnest curiosity which sometimes made him seem simple. He often accompanied his father in later years, fetching water in the pot that was becoming too heavy for the old man, and listening to his lilting bray like a bird's cry: "Have-some-hot tea, sir! Have-some-hot tea, ma'am! Wondrous fine, one dross a cup" Ebsin loved his father and his siblings, and loved seeing the customers sigh with contentment as they sipped from the little silver cups which dangled from the chaiwala's cart on long chains.

But no amount of love can forestall the ending of things, and one day—after the festival of harvest had welcomed in the new year—the tea seller died. He had been honest, but he had also been poor, leaving only his chaiwala's equipment and supplies, and the robe he'd worn every day as he strolled the streets selling tea. As was the custom at the time, the eldest child chose first what she wanted to keep of the bequeathment.

After looking over the meager possessions, the donkey's daughter decided to keep the iron brazier, copper pot, and silver cups to sell for scrap. Satisfied with her share, she handed the rest to Ebsin's older brother. He took the remaining store of his father's tea bricks to sell to a tavern and defray his tab, then handed the remaining portion to the third child. Sniffling and grateful for even such small tokens, Ebsin kept all that was left: the black and white kimono his father wore every day, and a small necklace in the shape of a brass teapot, its thin leather cord still smelling faintly of the donkey's sweat.

The chaiwala was buried in a pauper's grave in the cemetery grove outside the city walls. His will had instructed his children to stand vigil for three nights, so that first evening the mismatched trio came together over the mound, without even a footstone to mark it. "Are you sure this is the right one?" the older brother asked; he had been drunk at the tiny funeral ceremony, and afterward had likely drank more because he still swayed a bit on his feet.

"Yes, I'm sure because he's next to this apple tree," Ebsin said, placing a hand on the rough and twisted bark. "Just imagine how this will look come spring, with the grass growing up and the flowers dusting across him." He hugged his father's kimono around his body: it was warm against the evening's rising chill, and anyway was the nicest clothing he owned; the tradition at the time being that one should stand vigil as though waiting to meet a king.

"Don't be morbid," the sister scolded, suppressing a shudder that might not have been from the chill gusts blowing over the graves.

They settled down on folded cloths, as much to protect their clothes from the dirt as their bones from the cold ground, and began the vigil. A nearby cabinetmaker's grave had a table-shaped footstone, and soon Ebsin's siblings were using it as though it were a table in a cozy parlor, rolling loud-clattering dice across its flat top. Unable to afford a glow crystal—what was back then a rarity and a luxury—they had set an oil lamp on the table-stone beside their dice, which flickered with every breeze or flutter of a sleeve. While they were thus entertained, Ebsin sat facing their father's grave, trying to remember everything the donkey had ever said to him. Mild admonishments and sincere praises alike he recalled and cemented in his mind, wishing he had paper to write down the words, even if the sound of his father's voice now lived on only in his own memory.

The next night the sister didn't come. The polar bear said that she had been so tired after the first night's vigil that she'd been reprimanded; working as a low-level clark in the royal palace didn't permit much leeway for mistakes, and she could ill afford to lose more sleep or status. So the two men sat by the grave, the older brother again making use of the cabinetmaker's stone for a gaming table: this night he had brought a well-used pack of Hand Full cards, and spent the evening dealing out the cheap paper rectangles in threes and mumbling the prognostications he derived from their various combinations. Ebsin, meanwhile, filled the night with the memories of his father's actions, even more ephemeral than words, and even more meaningful.

The third night Ebsin was alone. His brother, he suspected, had been at his favorite tavern since evening (or possibly midday) meal, as was his habit. Having his tab paid off, at least partially, by the bricks of their father's tea made this an even more likely possibility. Ebsin sat in his spot and placed a hand on the mounded dirt. "I'm sorry they could not be here with us, Father," he said quietly. Though tears streaked the fur of his muzzle, he brightened the darkness by recalling the lives touched by the humble chaiwala, with his cheer and kindness as much as with his tea. Though he hadn't a dross of his own, Ebsin counted himself rich to have had such a father.

Gusts of winter were plucking the last leaves of autumn from the apple tree's branches when the sky brightened. A bird began tootling its song just as the first early rays of dawn streaked across the velvet sky, drawing nearer with each note before perching on a gnarled limb above Ebsin's head. It was a magpie, and its piping (with the same tune as father's "Have-some-hot tea, sir," call) made Ebsin smile with dewy eyes as he recalled the way the smart birds would follow his father around, chirping in response to his gentle voice, eager for crumbs of bread he always shared from his lunch.

Then the bird hopped onto the ground on the other side of the donkey's grave and spoke in a clear voice: "We will all miss him." The kimono was warm about Ebsin's body, despite the cold air seeping through its baggy sleeves, and there was almost a prickle where it rested across his shoulders and down his back. Shaking off the sudden chill, Ebsin looked at the magpie, certain that he'd been hearing things. As he watched, the bird fluttered away, then came back with one of the last lingering blooms of the season, placing it with all seriousness on the mound of dirt. Then it turned to face him. "It is good that you wear his robe," the magpie said in its sad singsong.

There was no denying what his ears heard nor his eyes saw, but he rubbed his face just the same, expecting that the bird would have vanished by the time he looked again, but still it stood, watching him. The only thing left to do was be polite. "Good morning, and thank you: I miss him too." The fox swallowed a wave of tears, feeling very small within the kimono, but the bird hopped closer.

"I do remember you, you know: you were always gentle, tossing bread crumbs instead of stones like other boys. But it's not only sentiment that bids me speak," it said. "Your father's kimono has certain powers, each of which will be unlocked by performing some duty while wearing it. That is why you can understand me: the first duty is that of diligence, standing vigil here as he wished, and the first power that you're rewarded with is the ability to understand the speech of birds."

Indeed, though Ebsin could still hear the songs of the birds waking for their day in the graveyard grove around him, he could also hear their words—boisterous as any town at marketday—as they scolded and enticed and proclaimed.

The magpie continued. "The kimono also has the ability to remain undamaged and unsullied, no matter what." So that's why father wore it every day, and why it never seemed to need washing or mending, the fox realized, the cloth's embrace was heavy with meaning as the bird elaborated. "You must complete all three duties before spring if you are to claim full ownership of this magical cloak, as your father did before you. If not, it will balk at your touch, refuse to be put on, and you will have to give it away so it might find someone else more worthy of its gifts."

Ebsin wrapped his arms around himself, one hand straying to the charm around his neck with its donkey-scented cord. "I would hate to lose it; apart from my necklace this kimono is all I have of his. Please, tell me how I might perform the remaining duties and be worthy of keeping it."

"I will, in exchange for the shiny you cling to."

The fox looked down at the charm resting on his palm. It was just a flat piece of brass, cut in the shape of a teapot's silhouette, the sort of thing a metalsmith might make in a few moments, cheap enough to be exchanged for a cup of tea or two. Its slow and subtle swaying against the chaiwala's coarse fur for untold years had smoothed the edges and given its surface a bright polish, making it exactly the sort of thing such a bird would want for its nest. Reluctantly he lifted the thong from his neck and presented it to the magpie. Bowing his head in supplication, he asked: "Please, friend bird, tell me what I must do."

A tiny black-scaled claw plucked the brass from the fox's hand, letting it gleam one last time in the morning sunlight before tucking it away behind a wing. "Your first duty was one of diligence," it said, as though reciting an incantation, "just so will your next be fortitude, and your third curiosity. Demonstrate that you have these virtues and you shall be rewarded as your father was." Without another word, it bowed its head to the fox, then to the donkey's grave, and then flew up, its feathers occasionally revealing a glint of yellowish metal. Eschewing the branches of the already leafless apple tree that stretched over the grave like a net, the magpie fluttered to a nearby pine, swiftly becoming a bit of darker shadow within the shade of its boughs.

There was nothing left to do at the graveside, so Ebsin bowed his head, saying a quiet prayer, and bade his father's bones goodbye.

Owning nothing but the clothes on his back, he returned to the city, passing through streets stilled as much by early snow drifts as the absence of his father's familiar cries. His way was slow, for the old tea seller's familiar customers noted the fox in the donkey's habitual kimono, and many on learning the sad news offered him a meal or a cup of tea, which Ebsin accepted with gratitude. He listened to their stories and fond memories of the chaiwala, adding each one to the picture in his mind like tokens on a shrine. At last, as early winter's early evening was dimming the sky above, he reached the elemental plaza.

He stood in the wind-swept open space, staring at the allegorical spire, the tentpole and touchstone of the city, and wondered what the fates had in store for him. His siblings had lodgings of their own, and the chaiwala's little apartment had already been sold to pay for the meager funeral. Though he would gladly have opened his own door to them, were their situations reversed, he suspected neither his sister nor his brother would welcome him as houseguest for more than a day or two. Better to make a start on finding his own way. He'd loved following his father on his rounds, taking over more of the duties as both donkey and fox grew older—the one weaker as the other grew stronger—but he could not be a chaiwala without tea, without pot and brazier and cups and cart. And, if he was honest with himself, without the older man's company it would not be the same.

He cast about for inspiration; a flutter of black and white—a magpie's wing?—drew his attention to one side of the plaza, where a sheltered board held notices and messages, stirred by the breeze. The largest such was what had drawn his eye, its beautiful calligraphy forming a regular pattern of black ink on white paper: it was a proclamation from the princess. "Loyal subjects," it began, "Princess Dolan hereby proclaims a general quest. Whereas Tenobrius is to stand apart and support itself as a just and true nation, the Throne therefore requires and commands all citizens to come to the aid of their home. Discover, create, or otherwise bring to the Throne such products of Nature, of Craft, of Art and Invention that may be unfound elsewhere in the world, that Tenobrius might thereby prove itself unique and potent. The reward shall—" But here the wintry wind, or possibly some careless hand, had torn away the last fingerlength of the paper, taking with it both the royal seal and the specifics of the reward. The paper itself was weathered and worn, and had likely been in place for a goodly long time.

Still, it had not been taken down, and lacking any other idea, the fox turned his steps south-west, toward the palace. He went to seek his fortune, as was so often done at the time, and was admitted through doors each bigger than a farmer's cart and along a hallway lit by the rare and expensive glow stones, into the throne room. Despite the lateness of the hour, there was still a queue of citizens: some clearly had ideas on claiming whatever reward had been promised by the proclamation, but most of the others had the quietly-angry look of those waiting to seek redress for grievances. Ebsin watched with curiosity as each one approached the young wolf sitting on the massive throne—she could have been no older than himself—and presented his or her case.

Princess Dolan listened with sage graveness to each offer or request, and rarely turned to the older man sitting in a smaller (but much more comfortable looking) chair beside her throne. This demon was the regent, ostensibly assigned by the neighboring city of Bayard to aid her in ruling after the death of her father the king. But even one so simple as the chaiwala's son could see that he was leaning over often, whispering unasked-for guidance in the wolf's ear: guidance often in opposition to her own conscience, if her expression were anything to go by. His long face and lanky body seemed more like a coiled viper beside her elegance than any sentient being, and Ebsin had heard mutterings from some of his father's customers that the demon clearly meant either to marry the princess or expose her as unfit to rule. His being sent by the nearby city-state was likely due to the machinations of some old and obscure treaty, but many of those mutterings had also mentioned the other town's interest in expanding its borders and influence.

Seeing the line of supplicants dwindling and containing nothing so threatening as simple farmers and the like, the demon whispered something in her ear and bowed his exit, moving with the hunched posture of someone who had overindulged at a banquet and whose body had finally caught up. Though his long torso was lean and wiry beneath his own white and gold robes, there was indeed the beginning of a paunch that gave credence to the alleged revels and indulgences. With the regent gone to visit one of the palace's garderobes, Princess Dolan seemed to relax, and actually smiled at the remaining few subjects as each approached. Ebsin was the last in line, and by the time he took his turn, the wolf was sitting comfortably on the throne that had earlier seemed more like a torture implement.

"Your Majesty," he began, spreading the sleeves and tail of the kimono across the flagstones as he bowed low, "my name is Ebsin. My father has recently died, and I have come to seek my fortune and to save our kingdom."

The princess didn't immediately answer his request, but instead looked about the throne room. Seeing that no other claimants remained, and that the regent had yet to return, she rose from her seat. Gathering her skirts, she descended and bade Ebsin to rise. "Perhaps you would like some refreshment? It has been a long day in a long series of such, and a request such as yours might be better served by a quiet chat over tea."

The fox's ears perked up at the offer, and he gratefully accepted with as elegant a bow as he could manage, nearly overtopping himself, but finally catching his balance with a frantic wave of his long sleeve. The flag-like flapping of the fabric drew Princess Dolan's attention, and she asked about it as they walked down a corridor and into a comfortable room with a small fire and thick-glazed window. Before he could answer, however, servants came in bearing a tea service and a tray with small sandwiches and a bowl of red fruits, which distracted her. "Ah, I thought we were out. These strawberries are from a city many stades away, please have some as a token of my generosity and hospitality."

Obediently, Ebsin took two of the little berries, slipping one into his pocket while savoring the other with obvious relish. But when she reached for the steaming teapot, he reached out as well without thinking, stopping only at the last moment before overstepping his bounds as a commoner. "Please, Your Majesty, allow me to serve you; my father was a chaiwala."

She nodded, sitting back as the fox performed the simple act with as much ceremony as he could manage. "You'd said your father had died," she asked as she accepted her cup.

Ebsin had to pause a moment, looking into his own cup's empty bottom while he collected himself, feeling suddenly as hollow as the porcelain. "Yes, Your Majesty, I am twice orphaned." He explained, finally pouring tea for himself. "I don't remember my original parents, but my true father was all the family I needed—him and my siblings." He didn't mention that his sister worked in the palace, wanting on the one hand to stand on his own merits, and on the other to avoid tainting her reputation in case he were to commit some royal blunder. Instead he poured his own tea and then told her about the old donkey, how he had been fixture of the city and a friend to his customers.

"Have-some-hot tea, ma'am," Princess Dolan said softly, the sing-song call sounding more like a distant lullaby, as though she'd only heard it from far away.

The fox whimpered and sniffled, but managed to smile against his tears. "That was him, the cry he would use to summon customers as he walked the streets. I know he lives on in their hearts and memories, but I miss him still."

Dolan nodded and sipped her tea, then lifted the pendant that dangled about her neck. It was a locket, and within was a minuscule painting of King Heraldo. The two bereaved youths examined it, the princess seeming to recall some happy memory, while Ebsin couldn't help noting that the tiny eyes displayed more tenderness than was carved in the bird-spattered statue standing outside the palace walls. His hand went to his own neck, then remembered what had become of his necklace. "This kimono is all I have of his."

The princess had been about to speak—whether to ask him more about his ideas for seeking his fortune or retell some cherished memory of her own father, he couldn't tell—when the regent burst into the room. The demon had the breathless flush of one who had just been frantically running, but his chest was calm and his face impassive. "There you are, Your Highness. I did not know you had a guest, I would have—" then he recognized the fox as one of the supplicants from before. "Ah."

"This is Ebsin," she said graciously, "he has come to seek his fortune and save our kingdom."

"Well, what a remarkable lad," the regent said, his voice dripping with sincerity. "My lady, it is late. Perhaps young Ebsin would deign to spend the night in my own palace, and we can all discuss his fortunes on the morrow. I can tell you have had a long and trying day, Your Highness," he added. Once again in the regent's presence, Dolan did indeed look as worn-down as an old millstone, as though his approach had blown out some spark within her. She agreed to his offer—as she had agreed to more and more of the demon's suggestions as the audience earlier had progressed, Ebsin had noticed—and bade the two men farewell.

They left the sitting room as servants bustled in to remove the tea things and prepare the princess for bed, Ebsin trailing behind the regent's spade-tipped tail. "My palace," he explained over his shoulder, "is newer; I'm sure you've seen its construction. As such it has many more rooms available for hosting guests, and is in my humble opinion far more comfortable than this drafty old pile." With the twists and turns of the ancient corridors, Ebsin was already lost, and soon they left by a small side-door that had only one sleepy-looking guard. Crossing the yard and out through the palace's wall, they soon arrived at the regent's palace.

Like all buildings in Tenobrius, whether the mansion of a nobleman or the hut of the poorest villager, Norberth Palace was a round building—built around a central hearth as houses in warmer climes have their attention turned to an open courtyard—but it was large enough to have berths for ships where it straddled the harbor and a roof as big as the nearby elemental plaza. The only structure in the city that was bigger was the regent's own palace, new-built and reeking of resinous pine; its outside still had yet to be covered in the pebbledash plaster that coated every other structure, offering protection from cold and wet alike. Where the corridors of Norberth had been bright and airy, its beams and walls whitewashed repeatedly over the centuries, the regent's palace had a close-in feel, with narrow halls, high ceilings, and dark red lacquer beams still damp.

They passed workers still laboring over the structure, arranging furniture in rooms that had yet to be painted, carving beams that had already been set in place, and sweeping the floors that would likely be covered with sawdust again the next day. The regent nodded at all this busy activity, clearly pleased by how his palace was progressing. But Ebsin could see a frantic aspect to the laborers' motions, and was reminded of a bankrupt merchant he'd seen one day while out with his father. The horse had had poor luck and poorer prudence, and his every possession was therefore being carted up for sale to defray his debts, but the workers clearly didn't care what had value and what didn't: so crockery got jumbled with fire irons, books and artworks were tossed in with furniture, clothes which could have been used to pad fragile items were merely dumped on top of the pile; in short, motion and action were the watchwords, regardless of the quality or direction of such movement. Ebsin sniffed and rubbed his nose, irritated by the acrid construction smells and saddened when he saw wet lacquer dripping down an otherwise beautiful wall hanging, making it look as though it had been sprayed with fresh blood.

The room he was led to was just as half-done as the rest of the palace, its bare wood walls enclosing a lush woven rug, a golden bird cage, and a bed lacking any linen. The bird woke at the regent's arrival, but remained silent. "So, you seek your fortune?" the demon asked once he had closed the door behind him. "I imagine this urge is the result of Her Majesty's proclamation." There was scorn and frustration in his voice, for all his smiles.

"Yes, my lord. I wish to save our kingdom from its peril, to enable it to stand alone, sure and strong."

The regent snorted. "And I suppose, being a bright young lad, you know exactly how you'll set about saving Tenobrius?"

Ever truthful, Ebsin had to reply that he did not, not yet.

"Well, then let me save you the trouble. Here is a Maravelis, more than enough for a youth like you to seek his own fortune." He held up a triangle of gold, the coin clutched between the tips of his claw-like nails. Ebsin couldn't help but marvel at the wealth contained in that one little piece of metal: it was indeed more than enough to purchase a house, or buy back all the equipment and tea his siblings had sold and still have plenty left over. "All you need do," the demon continued, holding it just out of the shorter and younger man's reach, "is leave well enough alone, and stop bothering the princess with your childish hopes. She has enough on her mind without every citizen who can read responding to her proclamation with some wild scheme or impossible plan. You don't even have an idea, and yet you still came? The people of Bayard know better how to mind to their own business. Perhaps once she has given up her foolish ideas she will see that our way is far more efficient."

Ebsin glanced from the regent to the coin and back. The demon had started growing fat from old age as well as power, but there remained obvious strength in those limbs and belly from his youth as a soldier of Bayard. When the regent had first arrived, Ebsin had heard marketplace tales of how Princess Dolan's father had fought alongside the demon against the raiders that preyed upon the inhabitants around the Lucent Sea. He had been a worthy soldier and a competent general, so it was natural that he step into place after King Heraldo's death, using his skill to guide the princess until she became queen in her own right. But once the regent's palace had grown taller than the palace walls, the marketplace tales became back-alley mutterings. He might have been a good planner of battles, but there was hunger in those eyes now that Ebsin did not trust.

"No, my lord, I will not relent. There must be something even so lowly a citizen as I can do to help our princess."

The demon snarled, aristocratic face twisting into a gargoyle's predatory leer. "You might regret being so hasty. I'll let you sleep on your decision, O most welcome guest." And almost before the fox knew what was happening, the regent had slipped back through the door behind him, locking it from outside.

Ebsin sat on the comfortless bed, wondering at how things had gone so far astray. Moments before it had seemed he was gaining a friend in the princess, and even though he didn't have a single idea that could have helped the kingdom, it had still felt like he was doing good, if only by giving her a sympathetic ear. But now he was presented with a choice: if he insisted on going back to help her, he'd be forced either to come up with some brilliant plan or admit that he had none; on the other hand, if he took the regent's offer, he'd have more than enough money to build a life of his own, regardless of royal politics. What does it matter who is in charge, who's doing the ruling?

Of course, he knew that was a false question, and he recalled Dolan's soft grey eyes and the way they had lit up as the two orphans talked; he very much hoped that she would be the one in charge, and that she would be as wise and just a ruler as her father had been. The thoughts of family called to mind his sister; perhaps he might get word to her and seek help that way. But then he remembered that she worked at the queen's palace, not the regent's, and was likely to be at her lodging at that time of night. He also wasn't sure if she would help him; familial affection aside, she'd be more likely to scold him for trying to meddle, to fix too lofty a problem. Then a small sound interrupted his musings.

"It's so, so sad," the bird twittered from its cage, "if only I could warn him of the peril my master has planned for him."

Not wanting to be rude and eavesdrop, Ebsin cleared his throat. "Excuse me, friend bird, but what peril do you mean?" Then, to answer the bird's incredulous chirping, he explained about his fabulous robe. Smoothing down the front, he felt the lump of the strawberry in his pocket and offered it to the bird, which looked as though it had not been fed for days.

"Be careful," the bird warned after finishing its meal. "If he takes a little piece of wood from his pocket and waves his hand over it, you'll soon be engulfed in fire. He learned the spell while he was a soldier, and has used it often since then." There was a heavy sigh from the little feathery chest. "If only he had remained a soldier, we might yet have been happy. I perched on his shoulder and sang for him—even in battle—and he made sure I had the best from off his plate. But once I happened to chirp at just the wrong moment, and his robe caught fire instead of the logs he was trying to light. He's kept me caged ever since. That's how I know that the only way to stop him is to distract him as he's saying the last word."

Without thinking twice, Ebsin unlatched the door of the bird's prison. "Go, little one, your master does not deserve you." He picked the strawberry's top from amid the litter at the bottom of the cage, slotting the stem between his fingers and closing his fist around it; he wanted to be sure his improvised weapon—the only thing in the room that he could use for the purpose—was ready to hand. Once the bird was out, he closed the cage, trusting to the demon's confidence that he wouldn't even look twice. Then he opened the little window that let in cold starlight and let out the bird. "Thank you, my friend, fly well," he whispered as it winged through the evening air.

After a long and silent night, the regent came back. It was early in the morning, before any of the laborers had returned to continue their construction, and the demon again asked if his guest planned on remaining steadfast in his insistence to aid the princess. On receiving the fox's confident reply, he sighed dramatically. "I'll send her your regrets, then, seeing as you've been suddenly called away to a far-off land and will never return." He plucked a small plank of wood with a circle engraved upon it from one of the pockets of his robe. Ebsin couldn't be sure from where he was sitting, but it looked like a tiny version of the eight-pointed compass rose that decorated the paving stones about the central column of the elemental plaza outside. Exactly as the bird had said, the regent's other hand began moving in complex movements over the board.

The strawberry's top felt cool in Ebsin's fingers as he flicked it at the regent. It landed square on his brow, green leaves contrasting with red juice dripping down the dark crimson skin of his face. Concentration broken, the demon's gesturing hand juddered, lifting to his forehead to wipe away the berry, when suddenly flames began licking at the board he held. He tried to re-initiate the spell, but instead the magic redoubled, catching the sleeve of the regent's robe. White silk darkened, yellowing to match and then surpass the hue of its gold trim, wrinkling and charring even as Ebsin watched. A fragment of sumptuous fabric dropped to the rug below, flames catching on its thick threads before spreading to the bare and sawdust-strewn wood floor.

But Ebsin had already darted around his captor, resisting the impulse to help him douse the fire—after all, the fox hadn't been the one fooling with magic, hadn't been the one holding a young man prisoner (or trying to execute him) simply for wishing to help his princess—as he ran through the unlocked door. He felt the boards moving fast beneath his feet, his kimono billowing behind him like a kite in a breeze. The corridor opened up into the vast central space, which ought to have been warmed by the brick hearth rising like the core of an apple through the building, but (unlike the rooms and halls catching fire behind him) it was cold and unlit.

The flames licked fresh lacquer and roared with pleasure, a beast presented with a feast to slake its bottomless hunger. Ebsin's arms were stretched out to either side for balance as he ran along one of the galleries encircling the hearth room. Before he could stop his headlong pace, he saw that there was a section of unfinished balcony ahead of him, the break in the floor marked only by a yellow string that did nothing to prevent his passing right over it.

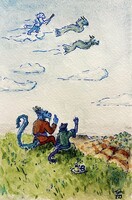

But still the red-lacquered railing continued scrolling past him, still the dark red beams flashed overhead. He looked down and saw that he was flying, the kimono stretching between his out-flung arms and back-thrust legs like the skin of a paper kite. The gallery's curve forced him to turn and he banked to one side—or perhaps it was the kimono turning for him, shifting his weight to make the maneuver as effortless and graceful as any bird's. He passed a wide and open door that looked into a ballroom, unevenly unfinished as was everything in the regent's palace, and the cold breath told him that the wide windows on its far side had not yet been installed.

Quick as thought, he flew out into the open air, looped around the hearth's thick brickwork column, and guided his path straight at the ballroom's door. Behind him the fire was spreading, and he could hear the demon's angry cursing and heavy hoofsteps pounding after him. But the regent had no magic kimono to let him fly straight across the empty heart of his palace, and his curses were mingled with coughs, his steps irregular as though he were sorely wounded. Ebsin couldn't spare even a glance backward as he swooped into the ballroom and out the glassless windows. He soared easily over the snow-dusted railing outside and heard a final cry from his captor before the roar of fire drowned out everything but the wind in the fox's ears.

A sudden gust turned him back toward the conflagration, and he saw that the whole structure was ablaze; he was grateful that he had freed the little bird. His path carried him over the building, and the updraft bore him higher than the treetops, higher than the tallest crystal spire out in the frozen wastes. He could see the little glimmers of the city waking up below him, hear the faint thread of sound from a fire alarm bell, but then the wind redoubled its efforts and blew him away from the streets and buildings he'd known all his life, out over the tundra.

The storm's breath also carried freezing sleet, which battled against the fire's tongues even as it pattered frostily against the back of Ebsin's kimono. Indeed, while the regent's palace burned down around the demon, it was only the sleet storm and the pebbledash of the surrounding buildings that saved the rest of the city from a similar fate. The gusting wind continued to carry Ebsin away as though he weighed nothing at all, until at last it deposited him wet and cold in an early snowdrift, somewhere in the crystal-speared wilds around Tenobrius.

Blinking and wiping the tears from his eyes (whether they stemmed from the wind or the smoke or the death of the regent, he couldn't tell), the fox saw a cave between two towering shafts of crystal. Like all children of his city, he had been warned from an early age of the dangers that lurked beyond the safety of Tenobrius—chief among which was the cold of the northern nights—so he knew that he needed to find shelter of any sort. With a prayer of thanks he slipped inside just as the storm resumed its wailing outside, battering against the massive crystal without so much as shaking off a pebble.

Ebsin found himself in a little natural anteroom, with a smooth sand-dusted floor and glassy walls. He was so exhausted by his recent ordeal that he was about to curl up in a corner away from the entrance...until a sliver of darkness caught his eye. Sitting up and tilting his head this way and that, he saw that what had at first seemed to be a shadowed corner was in fact another opening, leading down and away from the storm outside. Forgetting his fatigue for the moment, he poked his snout inside: the air was oddly warm, and there was a faint light further down. It seemed that he had stumbled on a deposit of glows, the crystalline chunks that produce a steady light so common these days, but back then were rare as talking frogs.

Indeed, the next little cavern had many of the fist-sized nodules scattered around. He could have used his kimono for a bag and carried away enough glows to make him rich for the rest of his days, but even as he began to slip his arm from its sleeve he felt a tendril of cold from the storm raging outside. "What good is a fortune when you're frozen solid?" he asked himself, pulling the kimono tighter around him. Instead he picked up only one, using it as a flameless torch while he continued exploring the cavern's depths. The next room had glitters of gold threading the crystal walls, and he was about to settle down on the floor to rest in its starry beauty when another breath of warm air drew him on to the next cavern.

Just as before, there were lumps and blocks and clods of crystal strewn across the floor like a handful of beads, each one faintly producing a soft warm glow like the sun shining through amber. Every stone also produced heat, as though it had been resting amid the embers of a hearth. Their combined output, however, had turned the cave into a sauna, so Ebsin plucked up a tiny pebble before scuttling back to the cooler comfort of the gold-veined room. The little stone in his hand was a much more comfortable warmth, and he soon fell asleep with the glow resting on the sand on one side of him and the pebble on the other.

When he woke, the storm had died away and the sun had risen over a quiet landscape peppered with sleet and hailstones—presage to the snows of full winter that would soon follow—through which thrust a last few defiant blades of grass amid the hardier tundra shrubs and mosses. A chill wind licked at his neck, but the pebble in his hand was warm and comforting. Looking around, he couldn't see any familiar landmark; having lived his whole life amid the streets and buildings of Tenobrius, he knew nothing of the wilds surrounding that outpost of civilized life beyond the terrors and yokai that populated fire-side stories and childhood cautions.

But the fox was not afraid. The storm may have blown him many stades from the city, but, as he said to himself: "If I got here from there, then I can certainly get there from here." He looked up at the towering crystals behind him with their treasure-laden cave. Perhaps, he thought, if they could be climbed, he'd be able to see far enough to know which direction to travel. He'd just begun a circuit of their bases in search of useful handholds—trying to recall when his brother had taught him how to climb trees in gladder times many years before drink had rotted the polar bear's heart—when he noticed an inky blot on the pinnacle of the tallest one. It was a bird, and, remembering the kimono's first gift, he called out to it in a friendly voice. "Excuse me, but can you see the city from up there?"

The bird tootled then spread its wings, gliding down in lazy spirals. "No, friend fox," it said when it had landed at his feet with a little hop. "But the kimono's third gift would allow you to fly even higher, and carry you straight back to your city." It was the same magpie that had first told him of the robe's magic while it perched in the branches above his father's grave

"The third gift? But I..." he paused, remembering the cave, with the tempting treasures he'd eschewed, as well as his miraculous flight from the regent's palace.

"The third gift," the magpie patiently explained, "is the power of disguise, allowing you to take on the form of a magpie. It was granted when you demonstrated curiosity, exploring deeper into the cave and finding your fate. The second gift," it continued, not giving Ebsin a chance to wonder what it had been hinting at, "was the power of flight. The kimono will catch you if you fall, and as you saw enabled you to soar through the air while still remaining your vulpine self. It was granted because you demonstrated the virtue of fortitude, standing firm against the easy path, no matter what the cost. Naturally, should you fail to demonstrate the three traits in the future, you will lose the powers tied to them."

"So I can fly home?"

"Precisely. The storm blew you east, so all you need do is wrap the kimono around you and think about becoming a bird, then fly straight ahead with the sun ever at your back." Then, putting its words into action, the magpie flew in the direction it had just indicated, leaving Ebsin once more alone.

Clutching the warm pebble in one hand, he used the other to pull the robe's heavy silk closer around his body and held the image of the magpie in flight in his mind. Swifter than a puddle in the summer, he shrank as the kimono tightened around him, squeezing his body effortlessly into the shape of a little bird. The pebble was now grasped by night-scaled talons, and when he stretched his arms two black-and-white wings spread wide. He gave his feathery tail a few flicks, then leapt into the air. His new body was so light that with a few flaps he easily rose above the pinnacle of the crystals that had sheltered him. Turning in the air so that the sun was as warm across the plumage of his back as the stone was in his claws, he saw a smudge in the distance: the remains of the regent's palatial pyre.

The wind seemed to be helping him along as he flew ahead, and it wasn't even midday before he soared over the smoking ruins of the regent's palace. The workers who days before had been building now cleared the rubble as the magpie flew across the sleet- and ash-drifted street to Norberth palace. Finding an open window in the upper reaches of the older building, he swooped in, navigated a few bright but empty corridors, and finally perched on the shadowed top Dolan's tall throne.

Now bereft of even the regent's dubious support, the wolfess had to stand on her own, and the disguised fox watches as she deals justly with the petitioners and functionaries in attendance—not as a princess, but as a queen come into her own. But as often as she was able to help them settle disputes or answer questions, however, just as often she had to them away with nothing, for no champion found to successfully answer her call. She seemed to fall into deeper despair with each denial, her heart breaking that she had too few resources to properly aid her subjects. She might also have been wondering why the friendly young fox had vanished along with the regent, and perhaps some of the worry that etched her face was the thought that both of them had perished in the fire.

Then, just as the chamberlain was announcing that the business for the day had been concluded, the little magpie hopped down from the shadows atop Dolan's tall throne, fanning its wings in a low bow before her as it grew, taking on the face and figure of the fox once more, the tail and sleeves of the magpie kimono spread out on the cold stones around him. He explained how he had escaped the regent's treachery with the help of his father's magic kimono, then presented the pebble, "Your majesty, I believe I have found something that might save Tenobrius." Still marveling at his sudden appearance, she took it in her hand, face softening at its warmth as he continued: "I found a cave, out in the wilds, where there are many more hot stones like this, as well as gold and normal glowstones."

"Such a find would truly be the salvation of our city. Imagine not needing fires and candles, our streets permanently lit and our houses forever warm. Imagine what the other cities might pay for such wonders!"

Sharing her smile, he held out his hand. "I'll need the pebble back, but I'll gladly go and bring back more, if I had a cart and a pebbleback to pull it."

Laughing, Queen Dolan handed back the warm little stone and told the fox to return the next day for the cart and draft animal and any tools he might need. With joy in his steps, and the pebble in his hand, Ebsin bowed to the wolf then trotted out of the palace and through the city until he came to the cemetery grove.

He knelt at his father's grave and told everything that had happened to him—as much to cement the details in his own memory as in the hope that somehow the old donkey might hear and be proud of his son—and was just finishing with his plans for the future that now looked so bright when he heard a twig snap above him. The magpie had perched in the same tree as before. "I have a gift for you," Ebsin said, "in gratitude for all of your help. I hope this will keep you and your nest warm all winter." He lifted his palm with the little thermal glow atop it. Without a word, the magpie snatched it and flew off to the pine, disappearing again in its darkened boughs.

Ebsin smiled and stroked the hem of his kimono, considering for a moment that he might transform himself again to follow the helpful bird into its hidden lair, but knew that would be unwelcome and rude. Instead, he rose and bowed to his father's bones, then turned to leave. A squawk above him drew his gaze back to the apple tree. The magpie was there with the donkey's necklace dangling from a talon. It dropped it into Ebsin's hands.

"Was that part of the test?" the fox asked, stunned after having been so certain he would never see the little brass teapot charm again.

"Maybe," was all the magpie said before it gave him a birdy wink and fluttered away.

True to her word, the next day the wolf gave Ebsin the pebbleback-drawn cart he needed to gather the first load of thermal glows, bringing them back and presenting the finest of the magic stones to her. She officially granted him a royal warrant, dubbing him thermal glow supplier by appointment to Her Majesty, Queen Dolan. When he was not mining the stones (or the gold around them) or exploring the wastes with the advice of the wild birds and in the form of a magpie himself to seek out other caves, he could be found at the palace. The queen often invited Ebsin to tea with her, and he would chat with her while pouring fresh brew into their cups, serving the way his father taught him, holding the magpie kimono looking as beautiful as ever.

With the money from what soon became a glow mining and export company, he was able to afford a footstone for father's grave. Taking inspiration from the cabinetmaker's monument, he had it carved in the form of a delicate-looking little table, on which sat a teapot and cup. Every tenday he would visit his father's grave, no matter the weather, bringing crumbs to place in the granite cup and saucer in continued gratitude to the birds that had shown him the way.

8,349 words, please view PDF for full text and proper formatting.

---

Back in the days when each city was a kingdom to itself, there lived in Tenobrius a chaiwala. This donkey's eldest daughter looked so much like his wife that he always smiled when he saw her. His second child was a polar bear, adopted when the cub's parents were lost at sea. His third child was a fox, likewise adopted and soon the most-beloved of all the donkey's children.

This young fox—Ebsin by name—had a true heart and an earnest curiosity which sometimes made him seem simple. He often accompanied his father in later years, fetching water in the pot that was becoming too heavy for the old man, and listening to his lilting bray like a bird's cry: "Have-some-hot tea, sir! Have-some-hot tea, ma'am! Wondrous fine, one dross a cup" Ebsin loved his father and his siblings, and loved seeing the customers sigh with contentment as they sipped from the little silver cups which dangled from the chaiwala's cart on long chains.

But no amount of love can forestall the ending of things, and one day—after the festival of harvest had welcomed in the new year—the tea seller died. He had been honest, but he had also been poor, leaving only his chaiwala's equipment and supplies, and the robe he'd worn every day as he strolled the streets selling tea. As was the custom at the time, the eldest child chose first what she wanted to keep of the bequeathment.

After looking over the meager possessions, the donkey's daughter decided to keep the iron brazier, copper pot, and silver cups to sell for scrap. Satisfied with her share, she handed the rest to Ebsin's older brother. He took the remaining store of his father's tea bricks to sell to a tavern and defray his tab, then handed the remaining portion to the third child. Sniffling and grateful for even such small tokens, Ebsin kept all that was left: the black and white kimono his father wore every day, and a small necklace in the shape of a brass teapot, its thin leather cord still smelling faintly of the donkey's sweat.

The chaiwala was buried in a pauper's grave in the cemetery grove outside the city walls. His will had instructed his children to stand vigil for three nights, so that first evening the mismatched trio came together over the mound, without even a footstone to mark it. "Are you sure this is the right one?" the older brother asked; he had been drunk at the tiny funeral ceremony, and afterward had likely drank more because he still swayed a bit on his feet.

"Yes, I'm sure because he's next to this apple tree," Ebsin said, placing a hand on the rough and twisted bark. "Just imagine how this will look come spring, with the grass growing up and the flowers dusting across him." He hugged his father's kimono around his body: it was warm against the evening's rising chill, and anyway was the nicest clothing he owned; the tradition at the time being that one should stand vigil as though waiting to meet a king.

"Don't be morbid," the sister scolded, suppressing a shudder that might not have been from the chill gusts blowing over the graves.

They settled down on folded cloths, as much to protect their clothes from the dirt as their bones from the cold ground, and began the vigil. A nearby cabinetmaker's grave had a table-shaped footstone, and soon Ebsin's siblings were using it as though it were a table in a cozy parlor, rolling loud-clattering dice across its flat top. Unable to afford a glow crystal—what was back then a rarity and a luxury—they had set an oil lamp on the table-stone beside their dice, which flickered with every breeze or flutter of a sleeve. While they were thus entertained, Ebsin sat facing their father's grave, trying to remember everything the donkey had ever said to him. Mild admonishments and sincere praises alike he recalled and cemented in his mind, wishing he had paper to write down the words, even if the sound of his father's voice now lived on only in his own memory.

The next night the sister didn't come. The polar bear said that she had been so tired after the first night's vigil that she'd been reprimanded; working as a low-level clark in the royal palace didn't permit much leeway for mistakes, and she could ill afford to lose more sleep or status. So the two men sat by the grave, the older brother again making use of the cabinetmaker's stone for a gaming table: this night he had brought a well-used pack of Hand Full cards, and spent the evening dealing out the cheap paper rectangles in threes and mumbling the prognostications he derived from their various combinations. Ebsin, meanwhile, filled the night with the memories of his father's actions, even more ephemeral than words, and even more meaningful.

The third night Ebsin was alone. His brother, he suspected, had been at his favorite tavern since evening (or possibly midday) meal, as was his habit. Having his tab paid off, at least partially, by the bricks of their father's tea made this an even more likely possibility. Ebsin sat in his spot and placed a hand on the mounded dirt. "I'm sorry they could not be here with us, Father," he said quietly. Though tears streaked the fur of his muzzle, he brightened the darkness by recalling the lives touched by the humble chaiwala, with his cheer and kindness as much as with his tea. Though he hadn't a dross of his own, Ebsin counted himself rich to have had such a father.

Gusts of winter were plucking the last leaves of autumn from the apple tree's branches when the sky brightened. A bird began tootling its song just as the first early rays of dawn streaked across the velvet sky, drawing nearer with each note before perching on a gnarled limb above Ebsin's head. It was a magpie, and its piping (with the same tune as father's "Have-some-hot tea, sir," call) made Ebsin smile with dewy eyes as he recalled the way the smart birds would follow his father around, chirping in response to his gentle voice, eager for crumbs of bread he always shared from his lunch.

Then the bird hopped onto the ground on the other side of the donkey's grave and spoke in a clear voice: "We will all miss him." The kimono was warm about Ebsin's body, despite the cold air seeping through its baggy sleeves, and there was almost a prickle where it rested across his shoulders and down his back. Shaking off the sudden chill, Ebsin looked at the magpie, certain that he'd been hearing things. As he watched, the bird fluttered away, then came back with one of the last lingering blooms of the season, placing it with all seriousness on the mound of dirt. Then it turned to face him. "It is good that you wear his robe," the magpie said in its sad singsong.

There was no denying what his ears heard nor his eyes saw, but he rubbed his face just the same, expecting that the bird would have vanished by the time he looked again, but still it stood, watching him. The only thing left to do was be polite. "Good morning, and thank you: I miss him too." The fox swallowed a wave of tears, feeling very small within the kimono, but the bird hopped closer.

"I do remember you, you know: you were always gentle, tossing bread crumbs instead of stones like other boys. But it's not only sentiment that bids me speak," it said. "Your father's kimono has certain powers, each of which will be unlocked by performing some duty while wearing it. That is why you can understand me: the first duty is that of diligence, standing vigil here as he wished, and the first power that you're rewarded with is the ability to understand the speech of birds."

Indeed, though Ebsin could still hear the songs of the birds waking for their day in the graveyard grove around him, he could also hear their words—boisterous as any town at marketday—as they scolded and enticed and proclaimed.

The magpie continued. "The kimono also has the ability to remain undamaged and unsullied, no matter what." So that's why father wore it every day, and why it never seemed to need washing or mending, the fox realized, the cloth's embrace was heavy with meaning as the bird elaborated. "You must complete all three duties before spring if you are to claim full ownership of this magical cloak, as your father did before you. If not, it will balk at your touch, refuse to be put on, and you will have to give it away so it might find someone else more worthy of its gifts."

Ebsin wrapped his arms around himself, one hand straying to the charm around his neck with its donkey-scented cord. "I would hate to lose it; apart from my necklace this kimono is all I have of his. Please, tell me how I might perform the remaining duties and be worthy of keeping it."

"I will, in exchange for the shiny you cling to."

The fox looked down at the charm resting on his palm. It was just a flat piece of brass, cut in the shape of a teapot's silhouette, the sort of thing a metalsmith might make in a few moments, cheap enough to be exchanged for a cup of tea or two. Its slow and subtle swaying against the chaiwala's coarse fur for untold years had smoothed the edges and given its surface a bright polish, making it exactly the sort of thing such a bird would want for its nest. Reluctantly he lifted the thong from his neck and presented it to the magpie. Bowing his head in supplication, he asked: "Please, friend bird, tell me what I must do."

A tiny black-scaled claw plucked the brass from the fox's hand, letting it gleam one last time in the morning sunlight before tucking it away behind a wing. "Your first duty was one of diligence," it said, as though reciting an incantation, "just so will your next be fortitude, and your third curiosity. Demonstrate that you have these virtues and you shall be rewarded as your father was." Without another word, it bowed its head to the fox, then to the donkey's grave, and then flew up, its feathers occasionally revealing a glint of yellowish metal. Eschewing the branches of the already leafless apple tree that stretched over the grave like a net, the magpie fluttered to a nearby pine, swiftly becoming a bit of darker shadow within the shade of its boughs.

There was nothing left to do at the graveside, so Ebsin bowed his head, saying a quiet prayer, and bade his father's bones goodbye.

Owning nothing but the clothes on his back, he returned to the city, passing through streets stilled as much by early snow drifts as the absence of his father's familiar cries. His way was slow, for the old tea seller's familiar customers noted the fox in the donkey's habitual kimono, and many on learning the sad news offered him a meal or a cup of tea, which Ebsin accepted with gratitude. He listened to their stories and fond memories of the chaiwala, adding each one to the picture in his mind like tokens on a shrine. At last, as early winter's early evening was dimming the sky above, he reached the elemental plaza.

He stood in the wind-swept open space, staring at the allegorical spire, the tentpole and touchstone of the city, and wondered what the fates had in store for him. His siblings had lodgings of their own, and the chaiwala's little apartment had already been sold to pay for the meager funeral. Though he would gladly have opened his own door to them, were their situations reversed, he suspected neither his sister nor his brother would welcome him as houseguest for more than a day or two. Better to make a start on finding his own way. He'd loved following his father on his rounds, taking over more of the duties as both donkey and fox grew older—the one weaker as the other grew stronger—but he could not be a chaiwala without tea, without pot and brazier and cups and cart. And, if he was honest with himself, without the older man's company it would not be the same.

He cast about for inspiration; a flutter of black and white—a magpie's wing?—drew his attention to one side of the plaza, where a sheltered board held notices and messages, stirred by the breeze. The largest such was what had drawn his eye, its beautiful calligraphy forming a regular pattern of black ink on white paper: it was a proclamation from the princess. "Loyal subjects," it began, "Princess Dolan hereby proclaims a general quest. Whereas Tenobrius is to stand apart and support itself as a just and true nation, the Throne therefore requires and commands all citizens to come to the aid of their home. Discover, create, or otherwise bring to the Throne such products of Nature, of Craft, of Art and Invention that may be unfound elsewhere in the world, that Tenobrius might thereby prove itself unique and potent. The reward shall—" But here the wintry wind, or possibly some careless hand, had torn away the last fingerlength of the paper, taking with it both the royal seal and the specifics of the reward. The paper itself was weathered and worn, and had likely been in place for a goodly long time.

Still, it had not been taken down, and lacking any other idea, the fox turned his steps south-west, toward the palace. He went to seek his fortune, as was so often done at the time, and was admitted through doors each bigger than a farmer's cart and along a hallway lit by the rare and expensive glow stones, into the throne room. Despite the lateness of the hour, there was still a queue of citizens: some clearly had ideas on claiming whatever reward had been promised by the proclamation, but most of the others had the quietly-angry look of those waiting to seek redress for grievances. Ebsin watched with curiosity as each one approached the young wolf sitting on the massive throne—she could have been no older than himself—and presented his or her case.

Princess Dolan listened with sage graveness to each offer or request, and rarely turned to the older man sitting in a smaller (but much more comfortable looking) chair beside her throne. This demon was the regent, ostensibly assigned by the neighboring city of Bayard to aid her in ruling after the death of her father the king. But even one so simple as the chaiwala's son could see that he was leaning over often, whispering unasked-for guidance in the wolf's ear: guidance often in opposition to her own conscience, if her expression were anything to go by. His long face and lanky body seemed more like a coiled viper beside her elegance than any sentient being, and Ebsin had heard mutterings from some of his father's customers that the demon clearly meant either to marry the princess or expose her as unfit to rule. His being sent by the nearby city-state was likely due to the machinations of some old and obscure treaty, but many of those mutterings had also mentioned the other town's interest in expanding its borders and influence.

Seeing the line of supplicants dwindling and containing nothing so threatening as simple farmers and the like, the demon whispered something in her ear and bowed his exit, moving with the hunched posture of someone who had overindulged at a banquet and whose body had finally caught up. Though his long torso was lean and wiry beneath his own white and gold robes, there was indeed the beginning of a paunch that gave credence to the alleged revels and indulgences. With the regent gone to visit one of the palace's garderobes, Princess Dolan seemed to relax, and actually smiled at the remaining few subjects as each approached. Ebsin was the last in line, and by the time he took his turn, the wolf was sitting comfortably on the throne that had earlier seemed more like a torture implement.

"Your Majesty," he began, spreading the sleeves and tail of the kimono across the flagstones as he bowed low, "my name is Ebsin. My father has recently died, and I have come to seek my fortune and to save our kingdom."

The princess didn't immediately answer his request, but instead looked about the throne room. Seeing that no other claimants remained, and that the regent had yet to return, she rose from her seat. Gathering her skirts, she descended and bade Ebsin to rise. "Perhaps you would like some refreshment? It has been a long day in a long series of such, and a request such as yours might be better served by a quiet chat over tea."

The fox's ears perked up at the offer, and he gratefully accepted with as elegant a bow as he could manage, nearly overtopping himself, but finally catching his balance with a frantic wave of his long sleeve. The flag-like flapping of the fabric drew Princess Dolan's attention, and she asked about it as they walked down a corridor and into a comfortable room with a small fire and thick-glazed window. Before he could answer, however, servants came in bearing a tea service and a tray with small sandwiches and a bowl of red fruits, which distracted her. "Ah, I thought we were out. These strawberries are from a city many stades away, please have some as a token of my generosity and hospitality."

Obediently, Ebsin took two of the little berries, slipping one into his pocket while savoring the other with obvious relish. But when she reached for the steaming teapot, he reached out as well without thinking, stopping only at the last moment before overstepping his bounds as a commoner. "Please, Your Majesty, allow me to serve you; my father was a chaiwala."

She nodded, sitting back as the fox performed the simple act with as much ceremony as he could manage. "You'd said your father had died," she asked as she accepted her cup.

Ebsin had to pause a moment, looking into his own cup's empty bottom while he collected himself, feeling suddenly as hollow as the porcelain. "Yes, Your Majesty, I am twice orphaned." He explained, finally pouring tea for himself. "I don't remember my original parents, but my true father was all the family I needed—him and my siblings." He didn't mention that his sister worked in the palace, wanting on the one hand to stand on his own merits, and on the other to avoid tainting her reputation in case he were to commit some royal blunder. Instead he poured his own tea and then told her about the old donkey, how he had been fixture of the city and a friend to his customers.

"Have-some-hot tea, ma'am," Princess Dolan said softly, the sing-song call sounding more like a distant lullaby, as though she'd only heard it from far away.

The fox whimpered and sniffled, but managed to smile against his tears. "That was him, the cry he would use to summon customers as he walked the streets. I know he lives on in their hearts and memories, but I miss him still."

Dolan nodded and sipped her tea, then lifted the pendant that dangled about her neck. It was a locket, and within was a minuscule painting of King Heraldo. The two bereaved youths examined it, the princess seeming to recall some happy memory, while Ebsin couldn't help noting that the tiny eyes displayed more tenderness than was carved in the bird-spattered statue standing outside the palace walls. His hand went to his own neck, then remembered what had become of his necklace. "This kimono is all I have of his."

The princess had been about to speak—whether to ask him more about his ideas for seeking his fortune or retell some cherished memory of her own father, he couldn't tell—when the regent burst into the room. The demon had the breathless flush of one who had just been frantically running, but his chest was calm and his face impassive. "There you are, Your Highness. I did not know you had a guest, I would have—" then he recognized the fox as one of the supplicants from before. "Ah."

"This is Ebsin," she said graciously, "he has come to seek his fortune and save our kingdom."

"Well, what a remarkable lad," the regent said, his voice dripping with sincerity. "My lady, it is late. Perhaps young Ebsin would deign to spend the night in my own palace, and we can all discuss his fortunes on the morrow. I can tell you have had a long and trying day, Your Highness," he added. Once again in the regent's presence, Dolan did indeed look as worn-down as an old millstone, as though his approach had blown out some spark within her. She agreed to his offer—as she had agreed to more and more of the demon's suggestions as the audience earlier had progressed, Ebsin had noticed—and bade the two men farewell.

They left the sitting room as servants bustled in to remove the tea things and prepare the princess for bed, Ebsin trailing behind the regent's spade-tipped tail. "My palace," he explained over his shoulder, "is newer; I'm sure you've seen its construction. As such it has many more rooms available for hosting guests, and is in my humble opinion far more comfortable than this drafty old pile." With the twists and turns of the ancient corridors, Ebsin was already lost, and soon they left by a small side-door that had only one sleepy-looking guard. Crossing the yard and out through the palace's wall, they soon arrived at the regent's palace.

Like all buildings in Tenobrius, whether the mansion of a nobleman or the hut of the poorest villager, Norberth Palace was a round building—built around a central hearth as houses in warmer climes have their attention turned to an open courtyard—but it was large enough to have berths for ships where it straddled the harbor and a roof as big as the nearby elemental plaza. The only structure in the city that was bigger was the regent's own palace, new-built and reeking of resinous pine; its outside still had yet to be covered in the pebbledash plaster that coated every other structure, offering protection from cold and wet alike. Where the corridors of Norberth had been bright and airy, its beams and walls whitewashed repeatedly over the centuries, the regent's palace had a close-in feel, with narrow halls, high ceilings, and dark red lacquer beams still damp.

They passed workers still laboring over the structure, arranging furniture in rooms that had yet to be painted, carving beams that had already been set in place, and sweeping the floors that would likely be covered with sawdust again the next day. The regent nodded at all this busy activity, clearly pleased by how his palace was progressing. But Ebsin could see a frantic aspect to the laborers' motions, and was reminded of a bankrupt merchant he'd seen one day while out with his father. The horse had had poor luck and poorer prudence, and his every possession was therefore being carted up for sale to defray his debts, but the workers clearly didn't care what had value and what didn't: so crockery got jumbled with fire irons, books and artworks were tossed in with furniture, clothes which could have been used to pad fragile items were merely dumped on top of the pile; in short, motion and action were the watchwords, regardless of the quality or direction of such movement. Ebsin sniffed and rubbed his nose, irritated by the acrid construction smells and saddened when he saw wet lacquer dripping down an otherwise beautiful wall hanging, making it look as though it had been sprayed with fresh blood.

The room he was led to was just as half-done as the rest of the palace, its bare wood walls enclosing a lush woven rug, a golden bird cage, and a bed lacking any linen. The bird woke at the regent's arrival, but remained silent. "So, you seek your fortune?" the demon asked once he had closed the door behind him. "I imagine this urge is the result of Her Majesty's proclamation." There was scorn and frustration in his voice, for all his smiles.

"Yes, my lord. I wish to save our kingdom from its peril, to enable it to stand alone, sure and strong."

The regent snorted. "And I suppose, being a bright young lad, you know exactly how you'll set about saving Tenobrius?"

Ever truthful, Ebsin had to reply that he did not, not yet.

"Well, then let me save you the trouble. Here is a Maravelis, more than enough for a youth like you to seek his own fortune." He held up a triangle of gold, the coin clutched between the tips of his claw-like nails. Ebsin couldn't help but marvel at the wealth contained in that one little piece of metal: it was indeed more than enough to purchase a house, or buy back all the equipment and tea his siblings had sold and still have plenty left over. "All you need do," the demon continued, holding it just out of the shorter and younger man's reach, "is leave well enough alone, and stop bothering the princess with your childish hopes. She has enough on her mind without every citizen who can read responding to her proclamation with some wild scheme or impossible plan. You don't even have an idea, and yet you still came? The people of Bayard know better how to mind to their own business. Perhaps once she has given up her foolish ideas she will see that our way is far more efficient."

Ebsin glanced from the regent to the coin and back. The demon had started growing fat from old age as well as power, but there remained obvious strength in those limbs and belly from his youth as a soldier of Bayard. When the regent had first arrived, Ebsin had heard marketplace tales of how Princess Dolan's father had fought alongside the demon against the raiders that preyed upon the inhabitants around the Lucent Sea. He had been a worthy soldier and a competent general, so it was natural that he step into place after King Heraldo's death, using his skill to guide the princess until she became queen in her own right. But once the regent's palace had grown taller than the palace walls, the marketplace tales became back-alley mutterings. He might have been a good planner of battles, but there was hunger in those eyes now that Ebsin did not trust.

"No, my lord, I will not relent. There must be something even so lowly a citizen as I can do to help our princess."

The demon snarled, aristocratic face twisting into a gargoyle's predatory leer. "You might regret being so hasty. I'll let you sleep on your decision, O most welcome guest." And almost before the fox knew what was happening, the regent had slipped back through the door behind him, locking it from outside.

Ebsin sat on the comfortless bed, wondering at how things had gone so far astray. Moments before it had seemed he was gaining a friend in the princess, and even though he didn't have a single idea that could have helped the kingdom, it had still felt like he was doing good, if only by giving her a sympathetic ear. But now he was presented with a choice: if he insisted on going back to help her, he'd be forced either to come up with some brilliant plan or admit that he had none; on the other hand, if he took the regent's offer, he'd have more than enough money to build a life of his own, regardless of royal politics. What does it matter who is in charge, who's doing the ruling?

Of course, he knew that was a false question, and he recalled Dolan's soft grey eyes and the way they had lit up as the two orphans talked; he very much hoped that she would be the one in charge, and that she would be as wise and just a ruler as her father had been. The thoughts of family called to mind his sister; perhaps he might get word to her and seek help that way. But then he remembered that she worked at the queen's palace, not the regent's, and was likely to be at her lodging at that time of night. He also wasn't sure if she would help him; familial affection aside, she'd be more likely to scold him for trying to meddle, to fix too lofty a problem. Then a small sound interrupted his musings.

"It's so, so sad," the bird twittered from its cage, "if only I could warn him of the peril my master has planned for him."

Not wanting to be rude and eavesdrop, Ebsin cleared his throat. "Excuse me, friend bird, but what peril do you mean?" Then, to answer the bird's incredulous chirping, he explained about his fabulous robe. Smoothing down the front, he felt the lump of the strawberry in his pocket and offered it to the bird, which looked as though it had not been fed for days.

"Be careful," the bird warned after finishing its meal. "If he takes a little piece of wood from his pocket and waves his hand over it, you'll soon be engulfed in fire. He learned the spell while he was a soldier, and has used it often since then." There was a heavy sigh from the little feathery chest. "If only he had remained a soldier, we might yet have been happy. I perched on his shoulder and sang for him—even in battle—and he made sure I had the best from off his plate. But once I happened to chirp at just the wrong moment, and his robe caught fire instead of the logs he was trying to light. He's kept me caged ever since. That's how I know that the only way to stop him is to distract him as he's saying the last word."

Without thinking twice, Ebsin unlatched the door of the bird's prison. "Go, little one, your master does not deserve you." He picked the strawberry's top from amid the litter at the bottom of the cage, slotting the stem between his fingers and closing his fist around it; he wanted to be sure his improvised weapon—the only thing in the room that he could use for the purpose—was ready to hand. Once the bird was out, he closed the cage, trusting to the demon's confidence that he wouldn't even look twice. Then he opened the little window that let in cold starlight and let out the bird. "Thank you, my friend, fly well," he whispered as it winged through the evening air.

After a long and silent night, the regent came back. It was early in the morning, before any of the laborers had returned to continue their construction, and the demon again asked if his guest planned on remaining steadfast in his insistence to aid the princess. On receiving the fox's confident reply, he sighed dramatically. "I'll send her your regrets, then, seeing as you've been suddenly called away to a far-off land and will never return." He plucked a small plank of wood with a circle engraved upon it from one of the pockets of his robe. Ebsin couldn't be sure from where he was sitting, but it looked like a tiny version of the eight-pointed compass rose that decorated the paving stones about the central column of the elemental plaza outside. Exactly as the bird had said, the regent's other hand began moving in complex movements over the board.

The strawberry's top felt cool in Ebsin's fingers as he flicked it at the regent. It landed square on his brow, green leaves contrasting with red juice dripping down the dark crimson skin of his face. Concentration broken, the demon's gesturing hand juddered, lifting to his forehead to wipe away the berry, when suddenly flames began licking at the board he held. He tried to re-initiate the spell, but instead the magic redoubled, catching the sleeve of the regent's robe. White silk darkened, yellowing to match and then surpass the hue of its gold trim, wrinkling and charring even as Ebsin watched. A fragment of sumptuous fabric dropped to the rug below, flames catching on its thick threads before spreading to the bare and sawdust-strewn wood floor.

But Ebsin had already darted around his captor, resisting the impulse to help him douse the fire—after all, the fox hadn't been the one fooling with magic, hadn't been the one holding a young man prisoner (or trying to execute him) simply for wishing to help his princess—as he ran through the unlocked door. He felt the boards moving fast beneath his feet, his kimono billowing behind him like a kite in a breeze. The corridor opened up into the vast central space, which ought to have been warmed by the brick hearth rising like the core of an apple through the building, but (unlike the rooms and halls catching fire behind him) it was cold and unlit.

The flames licked fresh lacquer and roared with pleasure, a beast presented with a feast to slake its bottomless hunger. Ebsin's arms were stretched out to either side for balance as he ran along one of the galleries encircling the hearth room. Before he could stop his headlong pace, he saw that there was a section of unfinished balcony ahead of him, the break in the floor marked only by a yellow string that did nothing to prevent his passing right over it.

But still the red-lacquered railing continued scrolling past him, still the dark red beams flashed overhead. He looked down and saw that he was flying, the kimono stretching between his out-flung arms and back-thrust legs like the skin of a paper kite. The gallery's curve forced him to turn and he banked to one side—or perhaps it was the kimono turning for him, shifting his weight to make the maneuver as effortless and graceful as any bird's. He passed a wide and open door that looked into a ballroom, unevenly unfinished as was everything in the regent's palace, and the cold breath told him that the wide windows on its far side had not yet been installed.