Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders, Malaya 1942

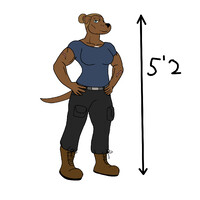

Alternate universe version of Duncan as a subaltern in the 2nd Battalion of the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders, somewhere in Malaya in January 1942. He appears to have wrangled a Thompson submachinegun for himself, but alas nothing can be done about the Desert camouflage he has been made to wear.

(and yes, I am aware his finger is inside the trigger-guard - that's actually accurate. Trigger discipline as we know it was non-existent in WWII. The heavy trigger pull of firearms in those days meant that long as your finger wasn't directly on the trigger, you were generally okay.)

The Highlanders were part of 12th Brigade, the only Indian Army formation in the Malayan Campaign that could fight the Japanese on equal terms. Led by Lieut-Colonel Ian Stewart (he was also, as the 13th Laird of Achnacone, a genuine Highland lord), the Highlanders had spent most of their time in Malaya training to fight aggressively through the jungles and dense brush along Malayan roads, supported by a squadron of armoured cars.

Unfortunately this proficiency, and that of the 4th Hyderabadi and 5th Punjabi battalions, led to 12th Brigade being used again and again to cover the withdrawal of the rest of Malaya Command. The Highlanders were whittled away in countless rear-guard and ambush engagements, until they were amalgamated with surviving Royal Marines from HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse to form the Plymouth Argylls Battalion. By the time Singapore was surrendered to the Japanese, the Highlanders and Marines had been cut down to less than a hundred men.

It's not usual I delve into historical art, but those who know me may not be surprised to know that my university studies were in military history. I mostly keep it separate from my interests on here, but I decided to indulge it for once.

(and yes, I am aware his finger is inside the trigger-guard - that's actually accurate. Trigger discipline as we know it was non-existent in WWII. The heavy trigger pull of firearms in those days meant that long as your finger wasn't directly on the trigger, you were generally okay.)

The Highlanders were part of 12th Brigade, the only Indian Army formation in the Malayan Campaign that could fight the Japanese on equal terms. Led by Lieut-Colonel Ian Stewart (he was also, as the 13th Laird of Achnacone, a genuine Highland lord), the Highlanders had spent most of their time in Malaya training to fight aggressively through the jungles and dense brush along Malayan roads, supported by a squadron of armoured cars.

Unfortunately this proficiency, and that of the 4th Hyderabadi and 5th Punjabi battalions, led to 12th Brigade being used again and again to cover the withdrawal of the rest of Malaya Command. The Highlanders were whittled away in countless rear-guard and ambush engagements, until they were amalgamated with surviving Royal Marines from HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse to form the Plymouth Argylls Battalion. By the time Singapore was surrendered to the Japanese, the Highlanders and Marines had been cut down to less than a hundred men.

It's not usual I delve into historical art, but those who know me may not be surprised to know that my university studies were in military history. I mostly keep it separate from my interests on here, but I decided to indulge it for once.

Category Artwork (Digital) / All

Species Unspecified / Any

Size 1920 x 1920px

File Size 478.4 kB

Oh, he was certainly to blame for the failure to train troops vigorously, and the failure to build adequate defences.

On the other hand, the lack of tanks basically doomed his defence from the start. It's pretty difficult to overstate the sheer tactical advantage the Japanese had over the Commonwealth, just by having tanks. They could move much more quickly at the tactical level, and could hit far harder on the attack. They could drive through ambushes and roadblocks, and cause havoc in rear areas.

The Commonwealth, on the other hand, had to be far more defensive than they would have been against an all-infantry adversary. Never a good idea to send infantry into the attack when there are enemy tanks nearby. They were also left at a huge psychological disadvantage, both at the tactical and the command level.

A single regiment of cruiser tanks, even relatively old ones like the A9 or A10, would have gone a very long way to levelling the tactical playing field.

On the other hand, the lack of tanks basically doomed his defence from the start. It's pretty difficult to overstate the sheer tactical advantage the Japanese had over the Commonwealth, just by having tanks. They could move much more quickly at the tactical level, and could hit far harder on the attack. They could drive through ambushes and roadblocks, and cause havoc in rear areas.

The Commonwealth, on the other hand, had to be far more defensive than they would have been against an all-infantry adversary. Never a good idea to send infantry into the attack when there are enemy tanks nearby. They were also left at a huge psychological disadvantage, both at the tactical and the command level.

A single regiment of cruiser tanks, even relatively old ones like the A9 or A10, would have gone a very long way to levelling the tactical playing field.

Given how stretched British resources were in the second half of 1941, it's questionable even if cruiser tanks would have helped; the RAF was also badly under-resourced, as well. And Percival wasn't alone in being inept; Brooke-Popham also deserves some blame, even though he did foresee some of what would happen. He was simply far too old to be put in his position. And factor in Tom Phillips' ineptitude (and arrogance) as well. You wonder if, even with the additional, hypothetical tanks, whether the high command in Singapore would have been able to use them effectively. (The Tommy on the ground is a different matter.)

I'm generally of the opinion that the flaws of Philips, Percival and Brooke-Popham are somewhat exaggerated. Once you actually look beyond the mythology and into the minutiae, it becomes clear that they really were prisoners of pre-war neglect, some very questionable judgement on Churchill's part, and appalling intelligence failures.

Philips, for example, only took Force Z north because the available intelligence assured him that the Japanese aircraft based in Indochina did not have the range to threaten his task force. Tragically, that was actually true until a few days prior to him setting sail. Once you bear that in mind, his decision makes far more sense. Drachinifel actually has an excellent video on why the destruction of Force Z was really the product of a Swiss-Cheese model of bad luck.

On the intelligence side, the Japanese had the advantage of having got their hands on a copy of the British defence scheme for Malaya, via a German U-Boat that had intercepted a British steamer.

Philips, for example, only took Force Z north because the available intelligence assured him that the Japanese aircraft based in Indochina did not have the range to threaten his task force. Tragically, that was actually true until a few days prior to him setting sail. Once you bear that in mind, his decision makes far more sense. Drachinifel actually has an excellent video on why the destruction of Force Z was really the product of a Swiss-Cheese model of bad luck.

On the intelligence side, the Japanese had the advantage of having got their hands on a copy of the British defence scheme for Malaya, via a German U-Boat that had intercepted a British steamer.

The thing that gives me pause in this vein is that you can have a general with a whole lot of terrible conditions, and still manage to do well in the long run. The example from the British Army in World War II, and Asia at that, is Bill Slim, who had to deal with terrible supply problems, awful terrain, and an aggressive (if stupid) opponent, and he still managed to have one of the best records of any British general in the war -- and without the swelled head of Montgomery.

This is not, of course, to say that the pre-war neglect in Malaya wasn't a factor. Nor the civilian angle to it (Duff Cooper was probably a net negative in his time there, and was lucky to get out when he did -- and he does have his defenders).

As much as I respect Drach, I think Phillips pushed his luck vastly further than he should have, and even if Intelligence hadn't picked up on the "new" planes coming in that had the range, that was still a probability he should have contemplated. Hindsight, 20-20, and all that. Still, by late 1941, experience in the Med. should have taught Phillips a few things.

This is not, of course, to say that the pre-war neglect in Malaya wasn't a factor. Nor the civilian angle to it (Duff Cooper was probably a net negative in his time there, and was lucky to get out when he did -- and he does have his defenders).

As much as I respect Drach, I think Phillips pushed his luck vastly further than he should have, and even if Intelligence hadn't picked up on the "new" planes coming in that had the range, that was still a probability he should have contemplated. Hindsight, 20-20, and all that. Still, by late 1941, experience in the Med. should have taught Phillips a few things.

I think we look at things from different angles.

My gut feeling is that Phillips made a calculated gamble that didn't pay off. He knew the Japanese had landed, and he knew that things were already going badly for the Army.

If he sailed north, he knew that there was a chance he could catch the Japanese transports and blow them out of the water, buying the Army vital time and disrupting the Japanese advance by destroying their transports and denying them reinforcements.

If on the other hand he held back, the Japanese would simply land as many troops as they liked and would seize the Malayan airfields, which would leave Phillips with no choice but to evacuate to the East Indies anyway, or else be sunk in Singapore harbour.

With hindsight an evacuation to the East Indies would have been the best option, but Phillips was an officer of the Royal Navy. What's more, he was by training a destroyer officer. Bugging out while the Army was in trouble was simply not an option.

My gut feeling is that Phillips made a calculated gamble that didn't pay off. He knew the Japanese had landed, and he knew that things were already going badly for the Army.

If he sailed north, he knew that there was a chance he could catch the Japanese transports and blow them out of the water, buying the Army vital time and disrupting the Japanese advance by destroying their transports and denying them reinforcements.

If on the other hand he held back, the Japanese would simply land as many troops as they liked and would seize the Malayan airfields, which would leave Phillips with no choice but to evacuate to the East Indies anyway, or else be sunk in Singapore harbour.

With hindsight an evacuation to the East Indies would have been the best option, but Phillips was an officer of the Royal Navy. What's more, he was by training a destroyer officer. Bugging out while the Army was in trouble was simply not an option.

FA+

FA+

Comments